Author

Isabelle Robinson

Abstract

Children with Down syndrome (DS), fragile X syndrome (FXS), or younger siblings of a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASIB) often exhibit atypical object exploration and social engagement, which can affect important learning opportunities. The purpose of this study was to examine group differences in social attention shifting and attentional disengagement between infants with DS, FXS, and ASIBs. This study utilized data from a longitudinal study collected from 12-month-old infants with DS (n = 13), FXS (n = 14), and ASIBs (n = 24). No group differences were seen for social attention shifting. However, infants with DS showed significantly worse attentional disengagement than infants with FXS or ASIB infants (p-values <.005). Differential patterns of association between attention and language abilities were observed across groups. Findings underscore the importance of attention as a developmental foundation and suggest there may be unique developmental pathways across different etiologies.

Introduction

Attention

Attention is the ability to remain alert and focus on a specific stimulus in one’s environment, be that another person or the object (Rezazadeh et al., 2011). Flexible attention is crucial to a child’s development, as it aids in inhibiting impulsive behavior, generating automatic responses, critical thinking, and learning (Rezazadeh et al., 2011). In order to learn from the environment, a child must be able to attend and flexibly shift attention across various stimuli in order to optimize learning opportunities. The ability to effectively attend to their environment requires that child employ both attention disengagement and attention shifting.

Attention disengagement is the ability to effectively terminate focused attention from a stimulus. Disengagement of attention facilitates the opportunity to attend to other stimuli in the environment. Persistent focused attention and the inability to disengage (i.e., sticky attention) can cause infants to miss important learning opportunities (Mcmorris, 2015). Often these learning opportunities help support various skills including language and developing conceptual information about objects (Charman, 2003). However, attention disengagement is not as complex as attention shifting because it does not require the refocusing aspect that is necessary for attention shifting (Fidler et al., 2019).

Attention shifting is the ability to shift one’s attention across stimuli. Past studies have operationalized attention shifting as, “the ability to flexibly reallocate attention within one’s internal and external environments to support goal-directed behaviors or meet task demands” (Pérez-Edgar & Fox, 2005; White et al., 2011). An example of attention shifting would be terminating attention from a non-social stimulus and refocusing attention on a social partner (i.e., social attention) (Leekam & Ramsden, 2006). A child’s compromised ability to respond to bids by a social partner around an object or event (i.e., attention shifting) can also prevent important learning opportunities from occurring, which is where infants assemble important social and linguistic information (Akhtar & Gernsbacher, 2007; Baldwin, 1995; Fischer et al., 2016; Hahn et al., 2018). Attention disengagement and attention shifting have major implications in a child’s cognitive development, particularly language development.

Attention to surroundings and interactions with others is a vital part of language development in infants, as it assists with the concept of word-object mapping (Morales et al., 2000). Interactions with caregivers at a young age allows infants to associate word meaning with objects around them (Morales et al., 2000). Children who are typically developing (TD) are able to effectively pay attention to their surroundings or shift their attention from one object/scenario to another, which promotes typical language development. They can develop both expressive and receptive language skills. In a study conducted by Yoder et al. (2015), expressive language was defined as language that is useful in articulating oneself, whether that be thoughts, emotions or other ideas. Conversely, receptive language is the way in which a child understands language (Children’s Minnesota, 2020). Difficulties with attention disengagement and attention shifting have potential implications for acquiring these language skills in early development.

Impaired attentional abilities limit a child’s exploration of the world around them, and thus hinder language acquisition (Fischer et al., 2016). Previous research shows that interactions with the environment, facilitated by flexible attentional processes, are important for a variety of outcomes including social engagement, language, and cognition (Baldwin, 1995; D’Souza et al., 2020; Stahl & Pry, 2005). In particular, previous research has shown that an infant’s attention to their surroundings is predictive their vocabulary skills later in life (Kristen et al., 2011). Infants at high risk for atypical developmental outcomes can experience difficulties with both attention regulation and language development (Cornish, 2004; Fidler et al., 2019). However, little work has examined these associations in certain high-risk populations, such as neurogenetic conditions and infants with high familial risk of autism.

Attention and Language Difficulties

Infants with neurogenetic conditions such as Down syndrome (DS) and fragile X syndrome (FXS) experience atypical neurodevelopment and developmental delays that result in difficulties with attention regulation (D’Souza et al., 2020; Fidler et al., 2008) as well as impaired language development (Hahn et al., 2016; McDuffie et al., 2017). These difficulties in attention regulation in DS and FXS likely contribute to the child missing information important for language development, such as object and action labeling, and taking cued social information that communicates meaning and learning reinforcement. The aims of this study included examining potential attentional differences in DS, FXS, and younger siblings of a child with autism spectrum disorder (ASIB), who are at high-risk for atypical development and autism (Bruyneel et al., 2019). All three of these groups are at a heightened risk of attentional difficulties, which may also relate to language skills differentially in each group.

Down Syndrome. Children with DS show heightened social attention when compared to their TD peers, meaning they fixate their attention on a person rather than an object (Adamson et al., 2010). Flexible attentional disengagement is critical for learning and the inability to disengage or shift their attention is referred to as ‘sticky’ attention (Fischer et al., 2016). ‘Sticky’ attention is observed through over-fixation on objects, and the inability to shift their focus to a new object when one is presented (Fischer et al., 2016). Infants with DS are less likely to exhibit ‘sticky’ attention to objects, but evidence indicates they may demonstrate ‘sticky’ attention to social stimuli (Fischer et al., 2016; Hahn et al., 2017). Less attention to objects at the expense of heightened social attention has potential implications for acquiring both receptive and expressive language skills. In terms of language, children and adults with DS are known to have more difficulty with expressive language than receptive language (Martin et al., 2009). Although some known contributing factors to expressive difficulties exist, like craniofacial structure, the relation of attention to receptive and expressive language in children with DS is less clear (Martin et al., 2009).

Fragile X Syndrome. Young children with FXS demonstrate less social attention with gaze avoidant behavior, as well as fixated interest on objects (Chernenok et al., 2019). This attentional profile, quite opposite to that of DS, poses its own potential developmental difficulties. Children with FXS are known to have ‘sticky’ attention, which can inhibit their ability to garner information from the world around them in such a way that they can make use of it. Language is also a particular area of difficulty for children with FXS that may be affected by limited capacity for attentional disengagement and social attention shifting (Bruner, 1975; Hahn et al., 2018; Harris et al., 1996; Loveland & Landry, 1986; McDuffie et al., 2017; Tomasello & Farrar, 1986; Tomasello & Kruger, 1992).

ASIBs. Children who have an older sibling that has been diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) have a 10-20% increased chance of being diagnosed with autism than children who do not (Bruyneel et al., 2019). While ASIBs have not formally been diagnosed with ASD, and may never be, impairments in social communication and language delays are often evident in ASIBs when compared to their peers who are typically developing (Hahn et al., 2017). Children with ASD begin to exhibit impairments around 12 months (Hahn et al., 2017). Infant ASIBs are less likely to exhibit ‘sticky’ attention than their peers with FXS, so attentional disengagement is not a known area of struggle for them (Fischer et al., 2016; Hahn et al., 2017). It has been observed that up to 40% of ASIBs will exhibit one or more forms of developmental abnormalities, including language delays (Hughes et al., 2019). Evidence of early attentional difficulties in this group may be indicative of elevated risk for ASD or may potentially account for language delays observed in infancy.

Project Goal

The current project aims to examine attention patterns in 12-month-old DS, FXS, and ASIB infants through three main research aims:

- Examine group differences in attention disengagement.

- Examine group differences in social attention shifting.

- Examine the relation between attention disengagement and attention shifting and concurrent expressive and receptive language, as well as identify differential patterns in these associations across the three groups.

Hypotheses

Because children with DS have increased social attention, it is hypothesized that they will display diminished social attention shifting given they are more likely to already be engaged with the examiner. Another expectation of this study was that children with FXS will have prolonged attentional disengagement compared to their DS and ASIB peers, showing less disengagement from objects and less attention shifting from objects to social stimuli. Children with ASD have been observed to exhibit ‘sticky’ attention, similar to children with FXS, so it was expected that ASIBs may exhibit a similar attention pattern to the children with FXS, with diminished disengagement from objects and diminished attention shifting from objects to social stimuli (Fischer et al., 2016).

Methods

Participants

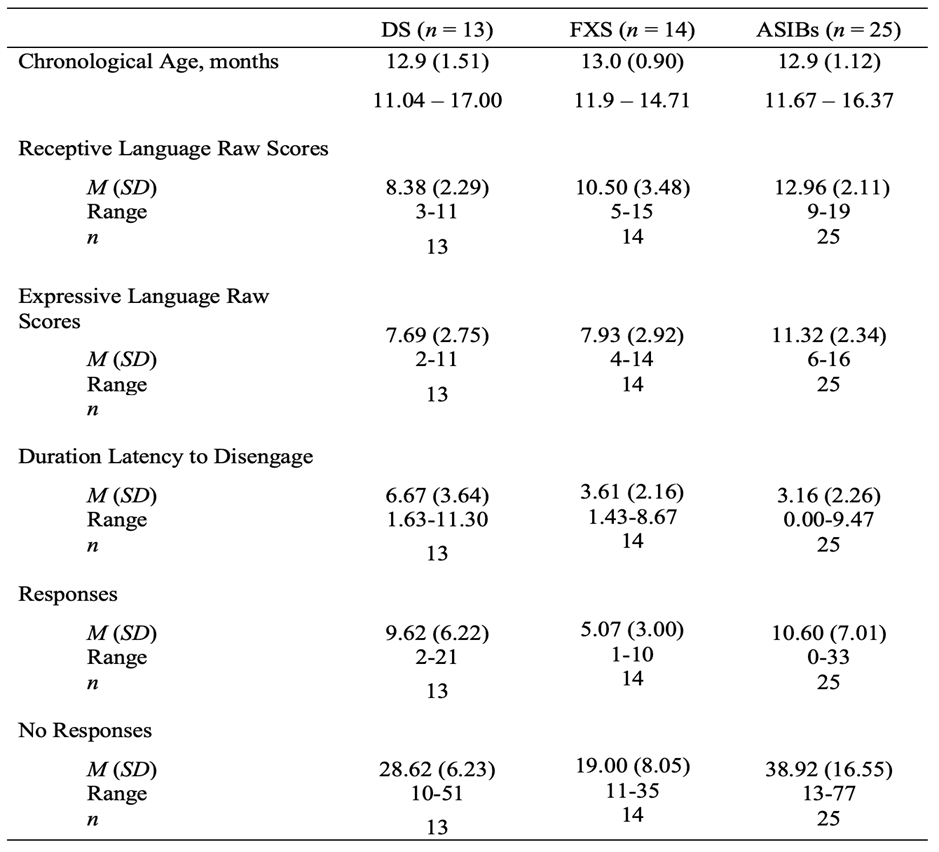

This study utilized extant data collected on 12-month-old infants with DS (n = 13; 62% male), FXS (n = 14; 71% male), and ASIBs (n = 25; 68% male). The participants for the current study were drawn from a larger longitudinal study on the development of children with neurodevelopmental disorders. The proportion of male participants across the FXS group is consistent with an X-linked disorder, and the ASIB group is predominantly male to match the FXS group per the larger study aims. The presence of DS and FXS was confirmed via genetic reports provided by the participants’ parents. Participants were included as ASIBs if they had an older sibling with a confirmed ASD diagnosis provided by the family and did not receive a later ASD diagnosis through the larger longitudinal study. Detailed participant characteristics are shown in Table 1.

Table 1

Participant Summary

Measures

Attention disengagement. Attentional disengagement was operationalized as the infants’ ability to shift attention from one object to another upon presentation of a novel object. Attentional disengagement was coded during the attention shifting task that occurs during the Autism Observation Scale for Infants (AOSI; Bryson et al., 2008). The Disengagement of Attention press consisted of three trials. Before the start of the first trial, the examiner ensured the infant’s full attention was on the first toy before activating a second toy. The trials were repeated two more times to examine the infant’s ability to shift attention between competing stimuli or toys (e.g., rattle, bell). All three trials were coded for attentional disengagement (i.e., latency of time for the infant to shift their attention from the first toy to the second toy) in seconds. A Total Attentional Disengagement score derived from summing the latencies, in seconds, across all three trials was used as a measure of attentional disengagement for analyses. Higher total latency scores reflect poorer disengagement. The AOSI was videotaped, and the Disengagement of Attention was coded offline using Noldus Observer XT (version 10.5, Noldus Information Technology, Leesburg, VA, USA). Attentional disengagement was coded by trained undergraduate research assistants. Initial reliability was established with a master coder by obtaining 80% agreement on three consecutive videos. In order to maintain reliability, 20% of videos were coded by a master coder, with Cohen’s kappa coefficients of .96.

Social Attention Shifting. For the purpose of this study, attention shifting between object and social stimuli was operationalized as the infants’ ability to respond to a verbal or nonverbal bid by the examiner (i.e., social attention shifting). Response was defined as the infant looking at the examiner’s face in response to the bid. No response was defined as the infants not looking at the examiner’s face in response to either type of bid. Attention shifting was measured during the first Free Play press of the AOSI. During the Free Play press, the infant was given various age-appropriate toys to play with, in whatever manner they chose, for 2 to 5 minutes. The infant was given multiple opportunities to respond to verbal and nonverbal bids from the examiner. A verbal bid was defined as any remark, vocalization, question, or request by the examiner made to engage the infant. A nonverbal bid was defined as any gesture by the examiner intended to engage the infant, such as pointing, showing, smiling, or touching the infant. For the current study, rate of response to examiner’s bid was used as a measure of social attention shifting for analyses. Rate of response to examiner’s bid was evaluated by dividing the frequency of response and frequency of no response by total response opportunities (i.e., all verbal and nonverbal bids). The AOSI was videotaped, and the first Free Play press was coded offline using Datavyu software (Datavyu Team, 2014). Social attention shifting was coded by trained undergraduate research assistants. Initial reliability was established with a master coder by obtaining 80% agreement on three consecutive videos. In order to maintain reliability, 20% of videos were coded by a master coder, with Cohen’s kappa coefficients of .81.

Language. The Mullen Scales of Early Learning (MSEL) was used as a measure of both expressive and receptive language ability. The MSEL is a comprehensive standardized developmental assessment that measures cognition, motor skills, and language abilities (Mullen, 1995). The MSEL assesses development across five domains: expressive language, receptive language, visual reception, fine motor, and gross motor. Total raw scores for the expressive and receptive language domains were used in analyses given the floor effects of standard scores in populations with intellectual disabilities.

Procedures. The AOSI and Mullen were administered as part of the same comprehensive developmental assessment. Participants were seen either at the participant’s home or at the lab, by at least two trained examiners. Written consent was obtained prior to the start of the data collection. All data used for the social attention shifting and attentional disengagement was coded using the videos from these assessments.

Statistical Analyses. SPSS 27 was used to run all statistical analyses. ANOVA analyses were used to test group differences in attentional disengagement and social attention shifting. Bivariate correlations were then employed to determine whether the patterns of association between attention and language varied across groups.

Results

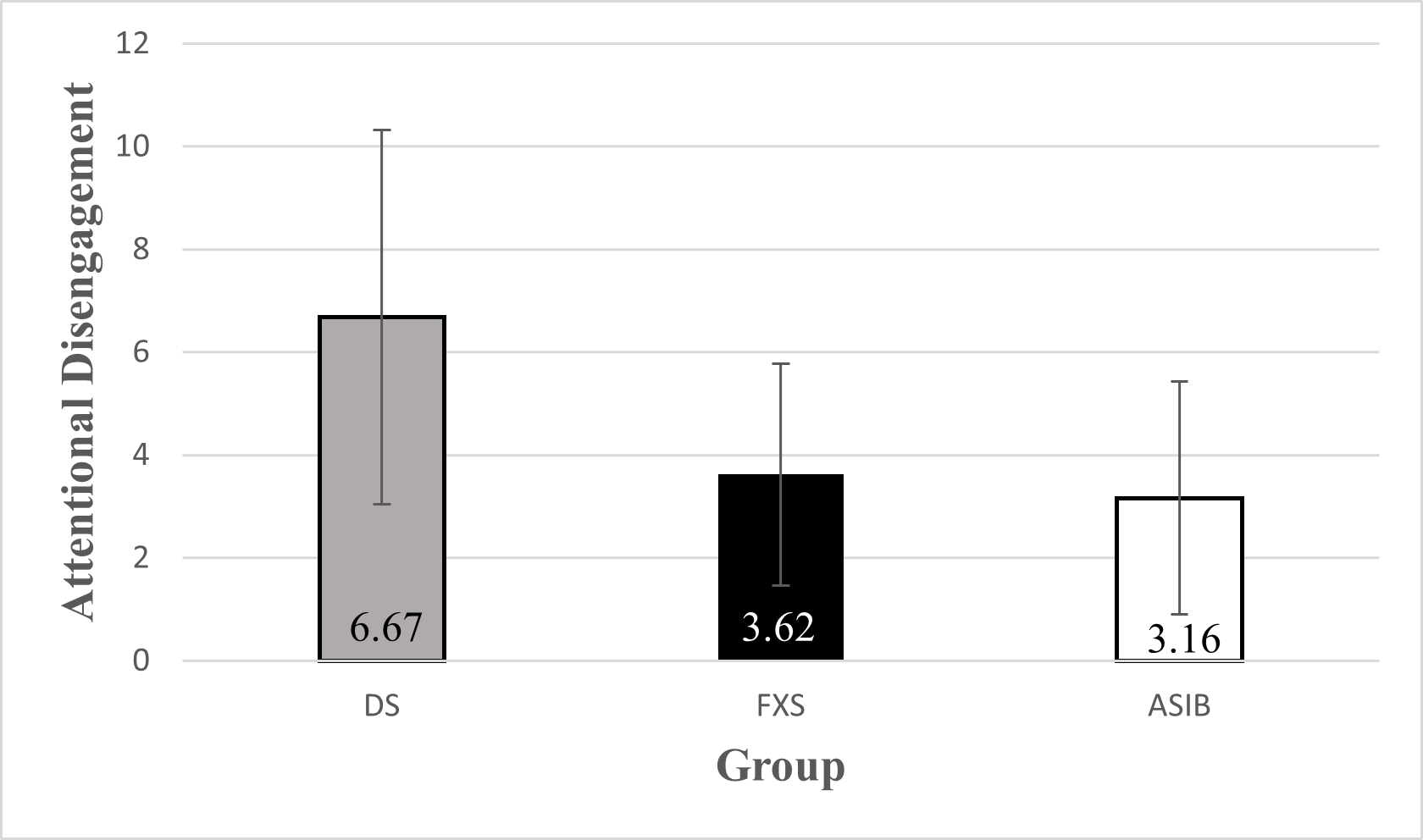

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post-hoc analysis was conducted to determine group differences in attentional disengagement as measured by Total Attentional Disengagement Score. Significant group differences were observed for latency of attentional disengagement, (F(2, 49) = 7.95, p < .001). Infants with DS took significantly more time to disengage than infants with FXS, (p = .004). Infant ASIBs took significantly less time to disengage compared to infants with DS, (p < .001), but not infants with FXS, (p = .609). These findings are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Differences in attentional disengagement between groups

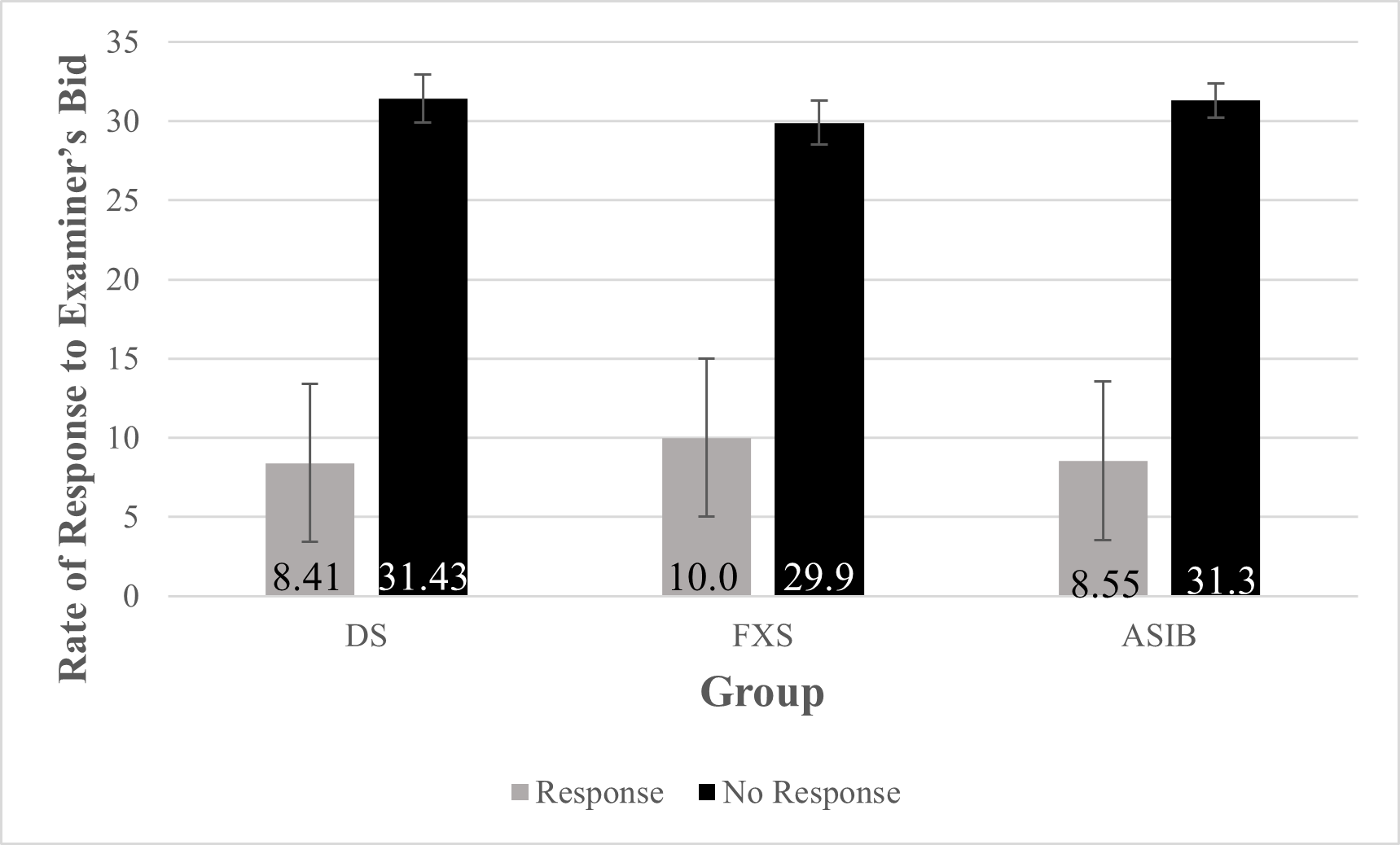

An analysis of variance (ANOVA) with Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) post-hoc analysis was conducted to determine group differences in social attention shifting as measured by rates of response to examiner’s bids. No significant group differences were observed for social attention shifting in frequency of response (F(2,48) = .421), or frequency of no response, (F(2, 48) = .421).

Infants with DS responded with the same frequency of response as infants with FXS, (p = .447), as well as infant ASIBs, (p = .946). They had the same frequency of no response as infants with FXS, (p = .447) and infants ASIBs, (p = .946).

Infants with FXS had the same frequency of response as infant ASIBs, (p = .431), and the same frequency of no response as infant ASIBs (p = .431). These findings are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2

Differences in Social Attention Shifting Between Groups

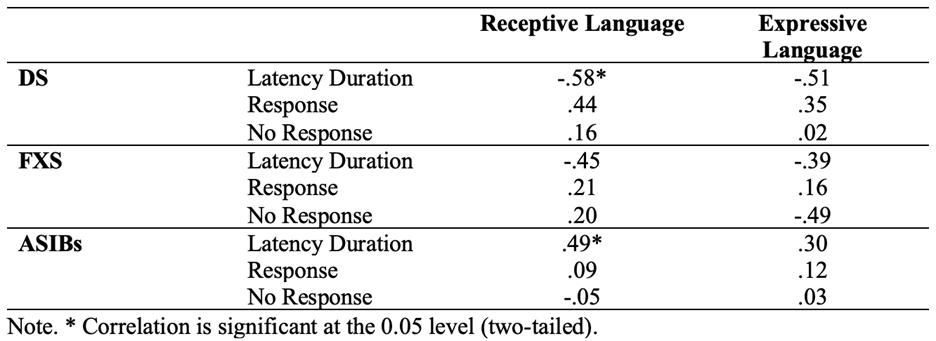

Patterns of association between attention disengagement, attention shifting, and receptive and expressive language were examined separately in each group through bivariate correlations. Across groups, different patterns of association emerged (see Table 2 for full correlation results).

For infants with DS, duration of attentional disengagement was significantly negatively correlated (r=-.58) with receptive language such that longer time to disengage attention was associated with lower receptive language. Duration of time to disengage attention was not associated with expressive language for infants with DS. Further, neither frequency of social responding or frequency of failure to respond were associated with expressive or receptive language abilities.

For infants with FXS, attentional disengagement was not significantly correlated with either receptive language or expressive language scores; however, time to disengage attention was moderately negatively associated with both expressive and receptive language scores (rs range -.39 - -.45) indicating that greater difficulty with disengaging attention is moderately associated with lower language scores for infants with FXS. There were no substantial associations between frequency of response and language sores for infants with FXS. However, although not statistically significant, there was a moderate association between no response and expressive language (r=-.49), such that greater frequency of no response moderately related to lower expressive language scores.

For infant ASIBs, attentional disengagement was significantly correlated with receptive language raw scores, (r=.49; p = .013), such that faster attentional disengagement was associated with higher receptive language. However, there was only a moderate to small non-statistically significant effect for expressive language (r=.30). No substantial associations were identified between frequency of response or no response and language scores for infant ASIBs.

Table 2

Correlations between receptive and expressive language, attentional & social attention shifting

Discussion

Infants with DS took significantly longer to disengage their attention from one object to the next one presented than infant ASIBs, which supported the original hypothesis. DS infants took the longest time to disengage from one object and look at the next object that was presented, and this difference was statistically significant when compared to infants with both FXS and ASIBs. This inability to flexibly shift attention may result in lost learning opportunities. These results do not support the hypothesis that FXS infants would have trouble disengaging due to ‘sticky’ attention. This study found that infants with DS had the greatest delay in disengaging their attention from one stimulus when another was presented. Infants with DS have been observed to have trouble disengaging from social stimuli, but these findings suggest that physical stimuli may also cause delayed disengagement in these infants (Fischer et al., 2016; Hahn et al., 2017). FXS and ASIB infants did not differ in their ability to disengage, suggesting that the ‘sticky’ attention that FXS infants have shown in prior research may not be evident at 12 months of age.

Results of this study reveal no significant differences in the rate at which DS, FXS, and ASIB infants respond to verbal and nonverbal bids from an examiner by shifting their attention. These results suggest that there was no difference in social attention shifting among the three groups.

When examining attentional disengagement and social attention shifting and their relation to language, results indicated that receptive language was correlated to attentional disengagement in DS and ASIB infants. These correlations indicate that ASIBs may not experience delays in attention, language, or information processing. Accordingly, the association may function differently for them given the delays present in the DS group. These results are consistent with the hypotheses and provide support for the notion that flexible attention has implications for their receptive language development. Both groups showed the importance of attention for language development, as longer times to disengage related to lower receptive language scores. These are potentially missed learning opportunities that could affect the infants for years to come. Further, the difference in these findings between the DS and ASIB group could be attributed to the difference in degree of impairment in both attention disengagement and receptive language in DS, and a lack of significant impairment in these areas for ASIBs.

This study did have several limitations including the lack of a TD control group and small sample sizes for the DS and FXS groups. Future work could include a TD control group to examine if there are statistically significant differences in attention patterns between TD infants and the infant ASIBs, since they are the least atypically developing group in this study. Future studies may also wish to use larger sample sizes, specifically from the DS and FXS groups, to increase statistical power. Addressing the limitations of this study in future studies could potentially bring to light more differences between the groups. Additionally, future studies could use different measures of engagement to see if there is a correlation between language and engagement that was not detected in this study. Further, since we know there are developmental delays in children with DS, FXS, and ASIBs, future studies could investigate where these delays may originate, if language impairments are not a strong contributing factor.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Dr. Jane Roberts, Dr. Elizabeth Will, Kayla Smith, and Ramsey Coyle for of their continuous advice and support in all aspects of this project.

About the Author

Isabelle Robinson

Isabelle Robinson

Isabelle Robinson recently graduated from the University of South Carolina Honors College with a degree in Biological Sciences. During her time at UofSC she worked in Dr. Roberts’ lab for three years being awarded the Exploration Grants two times and the Magellan Scholars Award as well. Upon graduation, she will be attending the University of South Carolina School of Medicine Greenville to pursue her M.D.

References

Adamson, L. B., Deckner, D. F., & Bakeman, R. (2010). Early interests and joint engagement in typical development, autism, and Down syndrome. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 40(6), 665-676. DOI 10.1007/s10803-009-0914-1

Akhtar, N., & Gernsbacher, M. A. (2007). Joint Attention and Vocabulary Development: A Critical Look. Language and linguistics compass, 1(3), 195–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00014.x

Baldwin, D. A. (1995). Understanding the link between joint attention and language. In C. Moore & P. J. Dunham (Eds.), Joint attention: Its origins and role in development (p. 131–158).

Bruner, J. S. (1975). The ontogenesis of speech acts. Journal of Child Language, 2(1), 1–19.

Bruyneel, E., Demurie, E., Warreyn, P., Beyers, W., Boterberg, S., Bontinck, C., Dewaelem N., & Roeyers, H. (2019). Language growth in very young siblings at risk for autism spectrum disorder. International journal of language & communication disorders, 54(6), 940-953.

Bryson, S. E., Zwaigenbaum, L., McDermott, C., Rombough, V., & Brian, J. (2008). The Autism Observation Scale for Infants: Scale development and reliability data. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 38(4), 731-738. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10803-007-0440-y

Chernenok, M., Burris, J. L., Owen, E., & Rivera, S. M. (2019). Impaired Attention Orienting in Young Children with Fragile X Syndrome. Frontiers in psychology, 10, 1567.

Charman, T. (2003). Why is joint attention a pivotal skill in autism? Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, 358(1430), 315-324. https://doi.org/10.1098/rstb.2002.1199

Children’s Minnesota. (2020). Receptive and expressive language. https://www.childrensmn.org/services/care-specialties-departments/physical-rehabilitation/receptive-and-expressive-language/#:~:text=Receptive%20language%20refers%20to%20how,Difficulty%20interacting%20with%20other%20children

Cornish, K., Sudhalter, V., & Turk, J. (2004). Attention and language in fragile X. Mental Retardation and Developmental Disabilities Research Reviews, 10(1), 11-16. https://doi.org/10.1002/mrdd.20003

Datavyu Team (2014). Datavyu: A Video Coding Tool. Databrary Project, New York University. URL http://datavyu.org

D'souza, D., D'Souza, H., Jones, E. J., & Karmiloff‐Smith, A. (2020). Attentional abilities constrain language development: A cross‐syndrome infant/toddler study. Developmental Science, e12961. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12961

Fidler, D. J., Most, D., Booth-LaForce, C., & Kelly, J. (2008). Emerging Social Strengths in Young Children with Down Syndrome. Infants & Young Children, 21, 207-220. doi: 10.1097/01.IYC.0000324550.39446.1f

Fidler, D. J., Schworer, E., Will, E. A., Patel, L., & Daunhauer, L. A. (2019). Correlates of early cognition in infants with Down syndrome. Journal of Intellectual Disability Research, 63(3), 205-214. https://doi.org/10.1111/jir.12566

Fischer, J., Smith, H., Martinez-Pedraza, F., Carter, A. S., Kanwisher, N., & Kaldy, Z. (2016).

Unimpaired attentional disengagement in toddlers with autism spectrum disorder. Developmental Science, 19(6), 1095-1103. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.12386

Hahn, L. J., Brady, N. C., Fleming, K. K., & Warren, S. F. (2016). Joint engagement and early language in young children with fragile X syndrome. Journal of Speech, Language and Hearing Research, 59, 1087-1098. https://doi.org/10.1044/2016_JSLHR-L-15-0005

Hahn, L. J., Loveall, S. J., Savoy, M. T., Neumann, A. M., & Ikuta, T. (2018). Joint attention in Down syndrome: A meta-analysis. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 78, 89-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2018.03.013

Hahn, L. J., Brady, N. C., McCary, L., Rague, L., & Roberts, J. E. (2017). Early social communication in infants with fragile X syndrome and infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 71, 169–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2017.10.004

Harris, S., Kasari, C., & Sigman, M. (1996). Joint attention and language gains in children with Down syndrome. American Journal on Mental Retardation, 100(6), 608–619.

Hughes, K. R., Hogan, A. L., Roberts, J. E., & Klusek, J. (2019). Gesture frequency and function in infants with Fragile X Syndrome and infant siblings of children with autism spectrum disorder. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 62(7), 2386-2399. https://doi.org/10.1044/2019_JSLHR-L-17-0491

Kristen, S., Sodian, B., Thoermer, C., & Perst, H. (2011). Infants' joint attention skills predict toddlers' emerging mental state language. Developmental psychology, 47(5), 1207. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024808

Loveland, K. A., & Landry, S. (1986). Joint attention and language in autism and developmental language delay. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 16(3), 335–349.

Leekam, S. R., & Ramsden, C. A. H. (2006). Dyadic orienting and joint attention in preschool children with autism. Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 36(2), 185–197. https://doi-org.pallas2.tcl.sc.edu/10.1007/s10803-005-0054-1

Martin, G. E., Klusek, J., Estigarribia, B., & Roberts, J. E. (2009). Language characteristics of individuals with Down syndrome. Topics in language disorders, 29(2), 112.

McDuffie, A., Thurman, A. J., Channell, M. M., & Abbeduto, L. (2017). Language disorders in children with intellectual disability of genetic origin. In R. Schwartz (Ed.). Handbook of Child Language Disorders (pp. 52–81). (2nd ed.). New York: Taylor & Francis. doi:10.4324/9781315283531-2

Mcmorris, C. A. (2015). Disengagement, Shifting and Engagement of Attention in Children and Adolescents With Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD).

Morales, M., Mundy, P., Delgado, C. E., Yale, M., Messinger, D., Neal, R., & Schwartz, H. K. (2000). Responding to joint attention across the 6-through 24-month age period and early language acquisition. Journal of applied developmental psychology, 21(3), 283-298. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0193-3973(99)00040-4

Pérez-Edgar, K., & Fox, N. A. (2005). A behavioral and electrophysiological study of children's selective attention under neutral and affective conditions. Journal of Cognition and Development, 6(1), 89-118. doi:10.1207/s15327647jcd0601_6

Rezazadeh, S. M., Wilding, J., & Cornish, K. (2011). The relationship between measures of cognitive attention and behavioral ratings of attention in typically developing children. Child Neuropsychology, 17(2), 197-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2010.532203

Stahl, L., & Pry, R. (2005). Attentional flexibility and perseveration: Developmental aspects in young children. Child Neuropsychology, 11(2), 175-189. https://doi.org/10.1080/092970490911315

Tomasello, M., & Farrar, M. (1986). Joint attention and early language. Child Development, 57(6), 1454–1463. https://doi.org/10.2307/1130423

Tomasello, M., & Kruger, A. C. (1992). Joint attention on actions: Acquiring verbs in ostensive and non-ostensive contexts. Journal of Child Language, 19(2), 311–333. doi:10.1017/S0305000900011430

White, L. K., McDermott, J. M., Degnan, K. A., Henderson, H. A., & Fox, N. A. (2011). Behavioral inhibition and anxiety: The moderating roles of inhibitory control and attention shifting. Journal of abnormal child psychology, 39(5), 735-747. doi:10.1007/s10802-011-9490-x

Yoder, P., Watson, L. R., & Lambert, W. (2015). Value-added predictors of expressive and receptive language growth in initially nonverbal preschoolers with autism spectrum disorders. Journal of autism and developmental disorders, 45(5), 1254-1270. doi:10.1007/s10803-014-2286-4