Author

Buffy Renea Duncan

Mentor

Jaclyn Wong, Ph.D

ABSTRACT

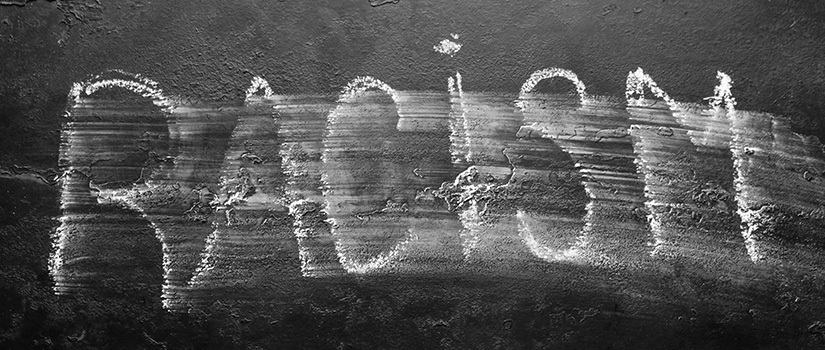

Despite the abolition of slavery and Jim Crow laws, racial inequity persists. Bonilla-Silva (2017) suggests that colorblind racism, or the assertion that race does not matter for one’s life chances, has perpetuated anti-Black racial inequality since the Civil Rights Movement. Now, through antiracist efforts such as the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, White Americans are increasingly expanding their notions of racism to include the subtle, institutional racial discrimination associated with colorblind ideologies (Crass 2015). A rejection of “colorblind” thinking places Whites in a position to address systems of White supremacy, both in themselves and the world around them, but it is not clear how this ideological shift influences antiracist activism. It is known, however, that when facing one’s own privilege, Whites often experience White fragility (DiAngelo 2018), a form of racial stress which can hinder antiracist efforts as Whites retreat from the discomfort they feel in race-based interactions. This study explores how White self-identified antiracists grapple with racial inequity and experience the challenges associated with changing views on race. Specifically, I ask: how do racially progressive Whites engage in everyday antiracism while managing White fragility? Interviews with self-identified politically liberal antiracist Whites show that some challenge systemic racial injustice by sharing antiracist ideas. Others struggle to process emotions like anger and fear around antiracist work leading to inconsistent engagement in antiracist action. Findings suggest that White people’s claims to being antiracist are centered on talk but not always larger actions.

INTRODUCTION

Despite the abolition of slavery and Jim Crow laws, racial inequity persists. In the United States, Black people have fewer opportunities for upward class mobility (Gaddis 2014), poorer health outcomes (Phelan & Link 2015), are incarcerated at exponentially higher rates (Bronson & Carson 2019) and are twice as likely to be killed by police (Fagan & Campbell 2020) than Whites. Some scholars suggest that colorblind racism, or the assertion that race does not matter for someone’s life chances, is the process perpetuating anti-Black racial inequality. Sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva (2017) describes colorblind racism as a set of nonracial explanations used by Whites which ignore the continuation of subtle, institutional racial policies and practices. He argues that colorblind racism conceals how institutional racial discrimination produces racial inequities by minimizing, naturalizing, and otherwise justifying racial differences in outcomes. So long as racial inequities are rationalized and overlooked, Whites can dismiss responsibility for addressing systemic racism. This nonracial ideology is apparent in slogans such as “All Lives Matter,” a counter-response to the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement, which aims to ensure freedom and justice for Black people (Black Lives Matter 2020). By removing race from the proclamation – a response that has been criticized by sociologists and racial justice leaders for ignoring the violence inflicted upon and the inequities experienced by Black folks (Agozino 2018; Burke 2018; Esposito & Romano 2016) – these Whites inhibit progress toward racial justice. While aspirational, identifying with “colorblindness” has not shown to have tangible outcomes in terms of interactions or policies that could reduce the effects of racial discrimination (Hartmann 2017). While many Whites hold fast to this ideology, some stand by the BLM antiracist movement and have come to understand the harm sustained through colorblind ideologies (Crass 2015) which overlook the true causes of racial injustice. According to Ibram X. Kendi, a leading scholar on antiracism, an antiracist understands that racial disparities are a result of racial discrimination (2016); they would be opposed to justifying inequities through colorblind logics. With a growing number of Whites now rejecting colorblind racism and endorsing antiracist ideas (Crass 2015; Kendi 2016) we might expect an increase in support of antiracist policies and practices. Indeed, 2020 saw a wave of antiracist protests that garnered increased White support across the nation after George Floyd, an unarmed Black man, was killed by police in Minnesota (“George Floyd” 2020). However, holding antiracist ideas may or may not impact the way Whites engage in antiracism in their day-to-day lives. It is also unclear whether Whites have the racial stamina needed to adequately address subtle racial discrimination.

With an increasing number of Whites rejecting colorblind ideologies and adopting a new racial worldview, it is possible they may experience race-based stress. Previous research indicates that when a long-held racial worldview is challenged, such as acknowledging the advantages of being White, Whites grapple with a discomfort known as White fragility often expressed through emotional displays of anger, fear, sadness, silence, and other defensive behaviors and claims (DiAngelo 2018). These responses serve to alleviate the unfamiliar stress associated with acknowledging White privilege and often leads Whites to disengage from cross-racial dialogue, and especially from consistent antiracist work. Hence, even as institutional racism is acknowledged, White fragility functions as a powerful influence in reproducing White privilege at the expense of Blacks. The recent surge in White antiracism may present issues of White fragility that White racial justice advocates are unprepared for, yet the implications of retreating back into the protective comfort of Whiteness are severe for Black Americans. Without Whites actively and consistently confronting institutionalized ideas and policies that lead to racial discrimination, we cannot hope to achieve racial equity.

In this interview study, I ask two questions: First, how do racially progressive Whites engage in antiracist activism in their everyday lives? And second, how do they manage White fragility as they undergo this work? For this paper, the term “racially progressive” is used to refer to those who reject colorblindness and see racial inequity as a direct result of discrimination, not those who simply claim to be non-racist (Hagerman 2017). Further, “everyday antiracism” refers to the ways we address racism in our day-to-day lives as opposed to isolated demonstrations such as attending a protest (Pollock 2008). Understanding the way Whites engage in antiracism will provide insight into the areas where progressive Whites can focus their antiracist efforts. Finally, by understanding how White fragility plays a role, we are in a position to identify continued obstacles to effective antiracism.

METHODS AND STUDY DESIGN

To answer these questions, I used qualitative semi-structured interviewing with nine White Americans who self-identified as antiracist to understand how they engage in antiracist activism in their everyday lives and how they manage White fragility. This method is ideal for understanding the way participants experience antiracism and White fragility in their social worlds. Questions centered around the interviewees day-to-day environments and activities with a focus on their racial ideologies and the initiatives they support or oppose within the organizations they are involved in.

I recruited participants by circulating a flyer on Twitter asking for White Americans (age 18+) who identified as antiracist and politically liberal. I chose to interview politically liberal Whites because they are generally seen as more race-conscious and have received less scrutiny than politically conservative Whites (Burke 2017). To explore how these individuals address anti-Black racial inequity in their daily lives, I gathered stories directly from them to detail their experiences. Semi-structured interviewing allowed me to systematically ask all interviewees a standard set of open-ended questions, but also gave me flexibility to probe for more information if an important topic came up for any individual interviewee. When participants recounted a personal story, particularly those where they expressed emotions related to White fragility, I asked them to reflect on their feelings and actions surrounding the situation.

Once participants were recruited, I conducted video interviews with each individual over Zoom. Using my interview guide, I asked questions relevant to my study, but otherwise kept the interviews conversational to allow important topics to emerge from the interviewees organically. Interviews generally lasted about one hour. I interviewed five women and four men between the ages of 29 and 50. Respondents were from Georgia, Michigan, South Carolina, California, Oklahoma, and Virginia.

I analyzed the interviews in two steps. First, I wrote a reaction memo immediately following the interview to capture the tone of the interview and anything that stood out as interesting, surprising, or especially relevant to answering my research questions. Then, I applied codes to sections of the transcripts using themes identified in the reaction memo and themes identified while reading through transcripts and connected each theme to a corresponding quote. To protect anonymity and confidentiality all names were changed to pseudonyms.

It is important to note that all interviews were conducted during the global Covid-19 pandemic when most people were experiencing a disruption in their day-to-day lives due to social distancing. Participants were asked to reflect on racial issues in their daily lives both before the pandemic and since it began. Additionally, the first four interviews took place in Spring 2020 and the last five interviews took place after the murder of George Floyd when antiracist protests erupted across the nation. Here, I distinguish between these two sets of interviews and refer to them as Spring 2020 and Summer 2020 interviews, respectively. These latter participants were also asked to consider and discuss their experiences before and after the protests began. The tone of these two sets of interviews were noticeably different, particularly in the manifestations of White fragility, and I make comparisons between them in my analysis.

EVERYDAY ANTIRACISM AND WHITE FRAGILTY

Five of these interviews took place during a major antiracist event, and here I distinguish between those conducted in the Spring, prior to the death of George Floyd, and those done in the Summer, after protests began. In general, racially progressive Whites seem to be good at talking about and expressing antiracist ideas but there is inconsistency in their activism. Participants rarely identified racism in their daily lives and preferred instead to discuss isolated, overt, or secondhand incidents. This may speak to the segregated lives that Whites live and point to colorblind racism as a potential barrier to identifying racial discrimination. When participants did identify racial discrimination in their community, they often did not act on it, speak out against it, or address it in any way. Reasonings around not addressing racism included fear, discomfort, and anger – all notable aspects of White fragility that lead to inaction among Whites (DiAngelo 2018). However, some participants did make an effort to work through strong feelings, such as sadness and guilt, in order to respond effectively. This shows that building stamina for White fragility is an important component of antiracist activism. The Spring versus Summer interviews show potential changes in both the expression of antiracism and White fragility. A larger pre- and post- sample size would be needed to determine this for certain. Here, I discuss the similarity and variability in these sets of interviews. Differences include a shift in the language used around racial categories with participants seeming more comfortable using the terms “Black” and “White” in the Summer interviews than those in the Spring; a change in the willingness to discuss one’s own internal biases and racist acts with Spring participants more likely to disclose their own biases than Summer participants; and a rise in emotional expression after the death of George Floyd.

Engaging in Everyday Antiracism

One prominent way that racially progressive Whites engage in antiracism is through having conversations with their friends, family, and coworkers. Discussions centered on education where spreading antiracist ideas are prominent and important themes. Participants described racial discrimination as being a systemic issue permeating every area of American society though it was rarely observed or noticed in their lives or communities. As such, taking proactive steps to combat systemic racism or taking action against instances of racism seemed optional, and often came with resistance or not at all. Charles, a 35-year-old retired police officer observed disparities in sentencing between Blacks and Whites with Blacks receiving harsher punishments than Whites for the same crime but did not feel empowered to address it. He retired from the police force and enrolled in school to study social work. When asked if he planned to use what he is learning in his social work program to help make changes within the criminal justice system he said that he did not. He believes the most important component of antiracism is a willingness “to have the talk.” When asked what this means, he responded:

The “talk” is “What is racism? What is antiracism?” You have to be able to explain [discusses at length examples of and stats around racial inequity] But, if you want to be active there’s plenty of organizations around that need participants, that need help.

For Charles, activism seems to be optional and potentially less important than discussions around racial inequities.

While participants mainly focused on sharing antiracist ideas as the primary means of engaging in everyday antiracism, there were a few good instances of participants identifying racial discrimination, even subtle discrimination, and taking direct action. Barbara, a 48-year-old woman with mixed-race children, told a detailed story about advocacy that led to positive change within her child’s school and his life. After teachers at a predominantly White school called a resource officer into the classroom to speak with her son and his best friend (also racially mixed) for arguing over a cell phone, Barbara wrote a letter to her son’s teachers. She believed they had good intentions but wanted to bring awareness to how their response was racially motivated and harmful. In writing the letter, she gathered allies including a parent, a teacher, a bus driver, and a community leader at another school who had dealt with a similar incident to read and discuss the letter before sending it. To ensure accountability, she copied these allies and the school principal on the email when sending it to the teachers. This prompted the principal to call a meeting that led to strengthened relationships between her son and the teachers, and the school later implemented unconscious bias trainings for staff and faculty. Finally, she affirmed her son’s experience by telling him that the discrimination he was seeing was real and empowered him with the tools to name it and call it out. Barbara discussed the concerns she had regarding speaking up but was moved to action by the desire for her son and his friend to be treated fairly. This illustrates the power of addressing subtle racism in a specifically antiracist way. It is also possible that Barbara’s interracial relationships with her family and with her peers contributes to her ability to more readily notice and respond to subtle racism than those Whites who live and work in more racially homogenous communities.

Everyday antiracism in Spring vs Summer 2020.

Because these interviews took place during a resurgence of BLM protests following the death of George Floyd, I was able to capture potential changes taking place in White antiracism. Interviews conducted in the Spring showed that racially progressive Whites signify their investment in antiracism by being intentional about the language they use around racial categories whereas participants interviewed in the Summer did not dwell on language. Here, Theresa, a 40-year-old woman from California requests “proper” terminology during a Spring interview, then answers her own question when talking about a coworker making racist jokes.

She would just make shitty jokes. I can’t think off the top of my head but if somebody who’s Hispanic has a picture of… I should be saying Latino. Is it Hispanic or Latino? I can say Latino.

Spring interviewee Shane, a 41-year-old man from South Carolina, wrestled with terminology and stopped to let me know that he was going to begin using terms that came more naturally to him, implying that it may be rude to call Black people Black and White people White.

Because growing up in [small southern town], I always felt like there was a significantly higher African American population than there were people of, whatever, white people. [pause] I use the terms white and black because that's how I grew up saying it, so that's what I'm going to say because nobody's ever going to listen to this but researchers.

It’s also noteworthy that Shane seemed to have handy terminology for Black Americans, but not for Whites, as Whites have little experience with seeing themselves as racialized beings. Interestingly, when asking participants their own race or ethnicity, only four of the nine answered with “White” despite the flyer explicitly asking for White participants. Three of the four “White” responses were from Summer interviews. Other responses were Caucasian, Irish American, and one detailed genealogy report. Spring participants often used the word Caucasian instead of White, potentially unaware of its connections to biological and political racism (Mukhopadhyay 2008). Jason, a 29-year-old man from Georgia, used it emphatically throughout the first half of his Spring interview, went back and forth between White and Caucasian midway through, and by the end had switched to using White entirely. Because he gradually shifted from saying Caucasian to saying White as he became more comfortable, we might assume that he saw the interview as a formal experience and initially wanted to reflect that by displaying his knowledge on matters of race. Alternately, participants in the Summer did not stop to consider the language they used around racial categories, relying seamlessly on the terms Black and White when talking. It is possible that the widespread and highly accessible conversations around racism in the last few months have enabled some Whites to speak more confidently about race, or more specifically to be more comfortable identifying as a racialized being. Further, in her book on White fragility DiAngelo discusses Whites tendency to see “others” as having a race, but not themselves. By not being racialized, Whites are protected from the effects of racism, relieved of responsibility for it, and maintain a position of status in a society centered around White norms (pp 24-28; 51-57). Strategies like this are functions of White fragility because they reinforce comfort for Whites and protect them from various levels of racial stress (p 122).

Managing White Fragility

With some exceptions, when participants observed racial disparities, they were often too uncomfortable to respond or consider changes that might foster racial equity. Reasons for inaction included claims such as fear of harm, discomfort associated with breaking social norms (like White solidarity), and feelings such as anger – each manifestations of White fragility (pp 57-59; 119-122). When Theresa, mentioned previously, explained why she never addressed her coworkers’ racist jokes she said, “If I made waves with her, it would just put the crosshairs on my forehead.” Theresa’s silence protected her reputation and potentially her job security yet did nothing to minimize the hostility present in her workplace.

Kayla, a 42-year-old woman from Oklahoma, did not want to “rock the boat” with her clients and coworkers. During a meeting, one of her clients announced that Kayla’s coworker was not welcome because they were Black. Kayla observed that most everyone in the room was White and chose to maintain White solidarity over addressing this issue. After reflection, she said that would likely do things differently in the future.

Finally, anger and sadness over witnessing racism also influenced one’s behavior. I include an analysis of anger and sadness as both obstacles to and motivators of activism in the following section because heightened emotions were a theme present in the Summer interviews, but not the Spring.

White fragility in Spring vs Summer 2020.

Manifestations of White fragility seemed to vary between Spring and Summer interviews. Participants in the first round of interviews volunteered stories of their own racial biases and microaggressions before I could even ask for them and generally expressed little to no emotion throughout the interview process. Alternately, participants in the second round of interviews rarely shared their own biases or mistakes, even when asked for them directly, and instead expressed a heightened level of emotional intensity over witnessing racism. It is possible that participants in the Summer felt triggered by consistent calls to antiracism.

Spring participants readily shared their own internalized racism and microaggressions, often unprompted, as if this admission was a key component of their antiracist work. Lana, a 42-year-old woman from Michigan talked about her unconscious biases while working on a project to educate people about the history of race riots in a Georgia town.

I didn't really realize that I was writing the narrative for white people. There's a way in which we make assumptions about what is known and what is unfamiliar. I was operating off of the premise that my audience was white without really even thinking about it.

Jason identified systemic racism as something he works to overcome in order to be brave enough to speak out against injustices.

The anxiety definitely comes from a place of fear of being afraid to have to confront someone and then the outcome of them becoming upset and something in my brain triggers that tells me they're going to hurt me, even though I could just be having a conversation. So I think for the longest time also I believe it was one of the most ingrained parts of my systemic racism that I had to overcome.

Theresa said she met a Black woman with mixed race children at her child’s school and asked her if her children had the same father.

Some people who have these racist tendencies don't realize they have the racist tendencies. Same with me, it didn't occur to me at the time I was being shitty to a woman with mixed race kids. I just said it because I have this internal racism that I'm not always aware of that's at work in my everyday life.

These stories and admissions of internalized racism from the Spring interviews were freely given as a way of illustrating that antiracism involves tough self-work like building racial stamina. These participants were quite comfortable telling these stories and seemed to accept their struggle as part of their personal growth.

Participants in the Summer interviews, however, were not as open about their own experiences of bias or racism and one even went so far as to deny the ability to engage in racist acts. When asked if he had ever been personally involved in an instance of racism, Charles replied, “No, because I come from a very liberal background.” When prompted, only one out of five participants admitted to being responsible for a racial microaggression and shared a personal story where they acknowledged their own bias. It may be that in the midst of this new civil rights movement it feels “unsafe” to express one’s own mistakes, preferring instead to claim racial innocence and protect and exempt oneself from responsibility by strictly being seen as an antiracist who has never engaged in anti-Black racism.

These participants from the Summer interviews also used strong sweeping emotions in the interviews to emphasize their antiracism. One participant expressed extreme residual anger in her interview while another expressed deep sadness. I highlight these two stories because they lead to different outcomes based on the management of these emotions. While such expressions may at times be a show of activism, I include them in the section on White fragility because they are a form of race-based stress with implications for White antiracist activism. Typically, anger is a defensive emotion that manifests when one’s own racist views are challenged but in one interview it was used to de-center the person harmed, and instead center the emotions of the White witness. Janice, a 50-year-old schoolteacher in Georgia, would often raise her voice, swear, or break down in tears when telling a story. Here she is recounting an incident that happened the previous school year where she witnessed a White boy withhold a valentine from a Black girl while waiting in the car line after school.

I just pulled her to me and I thought this boy's grandfather [pause] thinks he is not [raises voice] hurting anybody because he's a racist asshole at home and says this shit to his son and his grandson overhears him and he's breaking this little girl's heart. That boy's grandfather is breaking this little girl's heart right now and it makes me angry.

When asked how she responded she said she continued to hug the young girl while another teacher spoke to the boy’s grandparents when they arrived. She was thankful she did not have to talk to them because she believed her anger would have gotten in the way.

I am in a way glad because I don't think I would have responded very professionally to the parents. I would have said [very angry now] “where the fuck did he learn this? He learned this from you and he’s bringing it [voice shaking] and he's destroying people because of YOU and he’s here overhearing what you say and you think that it's… it's… it's right that you have a right to feel this way and that you're not hurting anyone and you are.”

Janice’s emotional responses illustrate the outrage that many antiracists feel when witnessing injustice. Unfortunately, in this case she allowed her anger to keep her from addressing the problem in any way other than comforting the young girl with a long hug. What struck me, was that after all this time she had still not processed her anger. It is possible that she sees the anger itself as a form of activism, rather than a simple manifestation of empathy or a form of White fragility masquerading as activism. Race-based stress responses have a racist impact when they inhibit antiracist activism.

Fortunately, not all emotionally charged responses led to inaction. Some made an effort to work through their feelings in order to respond effectively showing that managing race-based stress is an important component of antiracist activism. One interviewee told a profound story about his recent ideological shift from colorblind racism to antiracism. Brandon, a 45-year-old victim of police violence from Oklahoma, fought through discomfort throughout his interview. He had only identified as antiracist for a couple of months and still held many colorblind views, but he actively tries to change them. Here, he pushes through tears to recount the moment when his views changed.

I'm a victim of police brutality and until George Floyd I was a proponent of all lives matter because [sigh] there’s two sides of it. There’s the racists and there’s the victims that are saying “me too, what about me?” It happened to me and you're going to say “black lives matter” to me. […] And the way I was seeing it [pause, deep breath, long exhale] was that I was being denied my experience because I wasn't black. […] I wanted it to include me and these black people are saying “we want it to include us” and I don't know. […] Until I saw myself in George Floyd’s face and my kid [15 second pause where he cried in silence] in the video helped me [stop to gain control of breathing] made me identify [12 seconds, deep cries] made me see that [speaking with conviction now] the fastest way to save everybody is to save black people. We got to put them at the front of the line [choking on tears but speaking through them now] and if they don’t get it first then nobody else needs it, nobody else deserves it. If we don’t get behind them and all this momentum, I don’t know, it just changed the way I saw it.

Brandon used colorblind logics at various points in the interview, and admitted that he still struggles with understanding antiracism, but despite this he gave several examples of how he used his hurt and confusion to address racism. This is in stark contrast to those retreating from activism due to discomfort and from those claiming racial innocence to dismiss themselves of responsibility. Brandon created a sub-reddit dedicated to shining a spotlight on Black victims of police brutality. In doing so, he overcame the need for his own story to be told and instead brought attention to Black stories. When a Black friend of his posted to Facebook that she had been called a racial slur while walking in the park, he was angry. He messaged her to say what she endured was unacceptable, that she mattered, and he gave her his phone number and said if she experienced anything like that again to drop her location and he would come, no questions asked. He then shared her story, keeping her identity private, in a local BLM group to bring awareness to this happening at that specific park. Clearly, the Summer interviews were more emotionally charged and highlight the need for Whites to build racial stamina. Some Whites in the Summer round of interviews may see emotional responses themselves as a form of antiracist activism, rather than White fragility, while others push their way past them in order to bring about change.

CONCLUSION

This project aimed to answer two questions: 1) How do racially progressive Whites engage in antiracism? 2) How do they manage White fragility as they undergo this work? Interviews showed that racially progressive Whites engage in everyday antiracism primarily by talking with others about racism. Participants are aware of racial disparities, whether they personally witness them or not, and know how to talk about antiracism and racialized experiences in the abstract. But whether or not it is manifesting in day-to-day life is questionable in that they generally cannot give really good firsthand examples of racial discrimination to which they responded in specifically antiracist ways, nor describe what their antiracism looks like outside of conversations on race. Reasonings around not addressing racism include fear of retaliation, discomfort, and anger, though not all participants who experienced fear or heightened emotion, responded the same way. Some made an effort to move past their feelings in order to respond effectively.

Activists like Barbara, who advocated for change and empowered her son, and Brandon, who pushed past his grief provide examples of how to make antiracist policies and practices an everyday reality. However, between the common struggle to identify racial discrimination and the inconsistent way racially progressive Whites respond to racism, it may be overly optimistic to conclude these Whites are significantly improving racial equity. They do generally reject colorblind racism and maintain an antiracist outlook, but an important next step is proactively implementing change. What then can be done to move racially progressive Whites from simply having an antiracist mindset where they acknowledge that racial inequity is a product of discrimination into truly becoming active antiracists? If an antiracist is someone who not only expresses antiracist ideas but also supports antiracist measures (Kendi 2019), then the task for White antiracists is to curb their racial stress and engage in direct actions supporting their Black community members in interpersonal and institutional settings. Without these actions, racially progressive Whites risk causing further harm by acting out of heightened emotion or ignorance. Whites must dig deeper, stay in the fight, and actively work alongside Blacks to disrupt the racist systems of oppression present in themselves and in society at-large.

About the Author

Buffy Renea Duncan

Buffy Renea Duncan

Inspiration for my topic comes from an experience I had while serving on the Board of Trustees in a mostly White, antiracist identifying, interfaith congregation. I am White, and in 2017, alongside fellow faith leaders, I made a commitment to work toward dismantling White supremacy. White church members expressed concerns, beginning with the language “white supremacy.” Some thought it implied we were bad people and held fast to the notion that by not seeing color, we could not contribute to racial injustice. Over the course of a year, we experienced significant stress and frequently disagreed about where it came from or how to move forward. Admittedly, I often felt ill-equipped to understand the unfolding dynamics and this shortcoming may have contributed to an unsafe space for our members of color. When my time on the Board ended, I left for UofSC with a heavy heart. After taking courses like Antiracist Education and Unpacking Whiteness I no longer think our situation was unique. I believe that research such as this will enable Whites to move beyond passive resistance and become strong accomplices in dismantling White supremacy.

The paper submitted for this journal is part of a larger mixed-method project where I used quantitative analysis to identify who among Whites is most likely to hold antiracist views, and then I talked with them about antiracism. Working on and defending this thesis project in my senior year of college allowed me to graduate with distinction in Sociology and prepared me for graduate school where I plan to further my studies in race and education.

I cannot fully express how incredibly grateful I am to my committee members Diego Leal, Deena Isom Scott, and especially to Jaclyn S. Wong who served as chair. Jaclyn was incredibly motivating throughout this project and I could not have done it without her guidance, mentorship, and patience. I am also appreciative to the College of Arts and Sciences Undergraduate Research Enhancement Program for providing me with a grant to fund this research.

REFERENCES

Agozino, Biko. 2018. Black Lives Matter Otherwise All Lives Do Not Matter. African Journal of Criminology & Justice Studies. 11(1): I–XI.

Black Lives Matter. 2020. What We Believe. Retrieved on January 26, 2020. https://blacklivesmatter.com/what-we-believe/

Bonilla-Silva, Eduardo. 2017. Racism without Racists: Color-blind Racism and the Persistence of Racial Inequality in America. Rowman & Littlefield.

Bronson, Jennifer, and E, Ann Carson. 2019. Prisoners in 2017. U.S. Department of Justice. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Retrieved on January 26, 2020. https://www.bjs.gov/index.cfm?ty=pbdetail&iid=6546

Burke, Meghan. 2017. Colorblind Racism: Identities, Ideologies, and Shifting Subjectivities. Sociological Perspectives. 60(5): 857-865.

Burke, Meghan. 2017. Racing Left and Right: Color-Blind Racism’s Dominance across the U.S. Political Spectrum. The Sociological Quarterly. 58(2): 277-294.

Crass, Chris. 2015. Towards the “other America”: anti-racist resources for White people taking action for Black Lives Matter. Chalice Press.

DiAngelo, Robin. 2018. White Fragility: Why it’s so hard for white people to talk about racism. Beacon Press.

Esposito, Luigi, and Victor Romano. 2016. Benevolent Racism and the Co-Optation of the Black Lives Matter Movement. The Western Journal of Black Studies. (3):161.

Fagan, Jeffrey, and Alexis D Campbell. 2020. RACE AND REASONABLENESS IN POLICE KILLINGS. Boston University law review. 100(3): 951–1015.

Gaddis, Michael. 2014. Discrimination in the credential society: an audit study of race and college selectivity in the labor market. Social Forces. 93(4):1451-1479.

George Floyd, the man who’s death sparked US unrest. May 2020. BBC. Retrieved on July 23, 2020. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-52871936

Hagerman, Margaret Ann. 2017. White racial socialization: Progressive fathers on raising “antiracist” children. Journal of Marriage and Family. 79(1):60-74.

Hartmann, Douglas, Paul Croll, Ryan Larson, Joseph Gerteis, Alex Manning. 2017. Colorblindness as Identity: Key Determinants, Relations to Ideology, and Implications for Attitudes about Race and Policy. Sociological Perspectives. 60(5):866-888.

Hout, Michael. 2018. Americans’ Occupational Status Reflects the Status of Both of Their Parents. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Kendi, Ibram X.. 2016. “Prologue.” Pp. 2 in Stamped from the beginning: the definitive history of racist ideas in America. Words. New York: Nation Books.

Kendi, Ibram X.. 2019. “Chapter 1.” Pp 25 in How to be an antiracist. New York: One World.

Mukhopadhyay, Carol C.. 2008. Getting Rid of the Word ‘Caucasian.’ In Pollock, M. (Ed.). Everyday antiracism: Getting real about race in school. The New Press. Pp. 12-16

Phelan, Jo C., and Bruce G. Link. 2015. Is Racism a Fundamental Cause of Inequalities in Health? Annual Review of Sociology 41(1): 311–30.

Pollock, Mica. 2008. Everyday antiracism: Getting real about race in school. The New Press.