Author

Emma Doyle

Mentors

Melanie Palomares, Ph.D.

Psychology 228 (Laboratory in Psychology) is a capstone class for psychology majors and minors. The main goal of the course is the completion of an independent research project, which the student develops themselves from idea to data analysis over the course of the semester. The instructional team is led by faculty member Dr. Melanie Palomares and dedicated graduate students. The 2019-2020 graduate student team consisted of Wendy Chu, Kristin Kirchner, Samantha Langley, Jaleel McNeil, Jonathan Rann, and Daria Thompson.

Students were encouraged to develop a study based on their personal interests such as social media, interpersonal relationships, or exercise. Following certification in human subjects training, the students collected data by deploying surveys and assessments to their target demographic. Students analyzed and interpreted their data using SPSS, a statistical software. Students then wrote a full length, APA style research paper about their project. Students from this class acquired several skills such as responsible research conduct, survey creation, statistical software analysis, and professional writing. This class provided the opportunity for undergraduate students to preview the graduate student research experience. The students published here went the extra mile and prepared their research papers for this publication, which often included additional, more sophisticated data analysis and new research questions.

Abstract

Dating apps are increasingly popular among young people, including college students. However, these apps can be quite versatile, and there can be a number of reasons why a college student would use them, whether they are looking for a serious relationship, casual sex, or anything in between. Our study evaluated the intents, behaviors, and satisfaction of college students who used dating apps. Using Chi-Square and independent samples t-test analyses, results show that while satisfaction ratings were similar between men and women, more men use dating apps than women, which suggests that women might have a more negative perception of dating apps than men. Insights obtained through research such as this can be used in the future to improve the world of online dating, and facilitate connections between college students.

Connecting on Campus: Exploring the Motivations and Behaviors of College Students on Dating Apps

According to Pew Research, 30% of adults in the United States use a dating site or app (Anderson, Vogels & Turner, 2020). Dating and romantic relationships have intersected with the media in the past, beginning as early as the 1700s with the creation of personal advertisements in newspapers (Reimann, 2016). Throughout the modern world, technology has become more central in finding romantic relationships. Using the internet to form romantic and social connections is quickly gaining popularity, especially among college students (Stevens, 2006). On the one hand, even with the growing popularity of online dating apps, only 23% of those surveyed have reported actually going on a date as a result of using the dating site or app. On the other hand, 12% report finding a committed relationship or marriage from using the dating site or app (Anderson, Vogels & Turner, 2020). Thus, it seems that motivations and satisfaction for using these apps vary widely. According to a study about Tinder, a popular dating app, young adults, aged 18-30 years were motivated by the prospects of love, casual sex, thrill of excitement, and ease of communication (Sumter, et al, 2017).

The relatively low percentage of users who actually go on an in-person date suggests that the satisfaction from using dating apps might be variable as well. For example, many women have reported experiencing negative interactions, such as harassment and name-calling on the online dating platforms. Many men indicated that they did not get as many responses as they wanted from using dating apps (Anderson, Vogels & Turner, 2020). Moreover, users of dating apps also report that they expect that lying is a common occurrence in these platforms.

Among non-users of dating apps, there is a perception that online dating is not a safe way to meet people. Indeed, dating apps have been associated with a user’s intent to engage in acts of infidelity (Alexopoulos, Timmermans, & McNallie, 2020), which is likely associated with the scandal of the dating site, Ashley Madison, which specifically caters to people who are married or in relationships (CBS News, 2015).

Much of the present research on dating apps has studied young adult users, but not exclusively college students. College students are a population of particular interest because college is seen as an environment in which many people find romantic relationships. Due to this notion, people may wonder why college students would resort to using apps to meet others, when a college campus seems ripe with opportunities to meet people in person. Many different types of relationships between students can be observed on a college campus, from platonic friendships, to relationships based solely around sexual encounters, to very serious romantic relationships. Given this wide breadth of relationships within a confined community, coupled with the high usage of smartphones by college students, studying dating apps in the context of college campuses can divulge information about how the rapid expansion of technology is affecting campus climates and interpersonal relationships. Research into the relationships between college students and dating apps is essential in order to understand a new and growing part of life for many college students.

The current study evaluated the usage of online dating among undergraduate students at the University of South Carolina. College students are a population of particular interest, as technology and college life have become increasingly integrated in recent years (Dye, 2016). Moreover, the frequency of smartphone usage and sensation-seeking personality seem to be correlated with the intent (e.g., romance or casual sex) in college students who used dating apps (Chan, 2017). Based on previous research (Anderson, Vogels & Turner, 2020), we hypothesized that there will be differences between men and women in both their motivation for using dating apps, as well as the level of satisfaction obtained from using the apps. If this were the case, then compared to women, we would expect a disproportionate number of men to use dating apps, and would also expect them to report having different motivations for using the dating app.

Method

Participants

Sixty-nine college students from the University of South Carolina completed the online survey about dating app usage, who were recruited via social media. There were 43 females (M = 19.86 years, SD = 1.06) and 26 males (M = 19.73 years, SD = 0.92) in our sample. Racially, 57 people identified as White, seven as multiracial, three as Asian and two as Black. The majority of the responses were from Sophomores (55.1%), followed by Juniors (17.4%), Freshman (14.5%) and Seniors (13.0%).

Procedure and Analysis

A survey was created using Google forms, which was distributed via direct messages to other students on campus, as well as messaging groups of students on the messaging platform GroupMe. The survey included demographic questions (age, race, class, biological sex), and asked if they had used a dating app within the past 12 months. If participants had used a dating app in the past 12 months, they were asked what apps they used, for what reasons, how often they used the app, and they were asked to indicate their satisfaction in using the app(s) on a Likert Scale from 1-10.

Responses for motivations for using the dating app(s), included “Casual Dates” “Casual Sex” “A Serious Relationship” “Friendship” or “Other”. Respondents who selected “Other” could type in an answer of their own. For the purpose of this study, we have operationally defined the motivations. “Casual Sex” is defined as engaging in sexual acts without the explicit expectation of any sort of relationship to follow. The other responses were grouped to be in the non-casual sex category. “A Serious Relationship” is defined as an exclusive romantic relationship, typically with titles, such as boyfriend or girlfriend. “Friendship” is defined in our study the same way that it is defined and understood in current culture to be a non-romantic and non-sexual relationship. The responses to the motivation question were recoded to two categories, non-casual sex or casual sex, in order to distinguish the motivations based on primarily psychological versus physical intimacy. Using SPSS (IBM, 2019), Chi-square analyses and independent-samples t-tests were used to assess differences in the frequency of responses.

Results and Discussion

Who uses dating apps?

Out of 69 students, 45 reported using dating apps. The majority of students (93.3%) reported using Tinder. Other dating apps listed were Bumble (20%), Hinge (4%), Coffee Meets Bagel (2%), MeetMe (2%) and Grindr (2%).

In order to evaluate whether or not there were sex differences in who used dating apps (within the last 12 months), a Chi-square analysis was used. Out of 43 female participants, 20 stated that they used a dating app, while out of 26 males, 25 used a dating app, which indicated a significant difference in the frequency of the responses, 2 (1, N=69) =17.60, p<0.001. According to these counts (Figure 1), while there were more women who participated in the survey, a disproportionate number of men (96.2%) were using dating apps compared to women (46.5%). Interestingly, these results were different from those from Pew Research, which found that roughly equal proportion of men (32%) and women (28%) use dating apps (Anderson, Vogels & Turner, 2020). However our data are consistent with demographics reported by Tinder, the most popular dating site (Clement, 2020), Bumble, a site catering to women (Alter, 2015), and Hinge, a site specializing in serious relationships, (Carman, 2019), which reports 72%, 54%, and 64% male users, respectively (Clement, 2020, McAlone, 2015, Vedantam, 2020). It is noted that the data for percentage of male tinder users was Conspicuously, there were more male users than female users reported for Bumble, which is a site that is geared towards women. It is noted that the reported demographics of the Pew Research differ from those for the individual apps. A possible explanation for this disparity lies within the method of data collection. The data for the individual apps were collected via analytics, while the data in the Pew Research was collected via surveys. In addition, the Pew Research over sampled the lesbian, gay, and bi-sexual populations (Anderson, Vogels & Turner, 2020). It is possible that men and women equally use dating apps in the lesbian, gay and bisexual communities, however, since the data regarding Tinder, Bumble, and Hinge did not analyze the demographic of sexual orientation, it is unclear whether sexual orientation factors in to dating app usage.

Figure 1: Proportion of online dating users as a function of biological sex. A disproportionate number of males use online dating services compared to females.

What are the motivations of dating app users?

Since the number of male and female dating app users were uneven, then it is possible that there were sex differences in their motivation (i.e. casual sex or not casual sex) for using the app. We evaluated whether men and women listed “casual sex” as a motivation to use the app in different proportions. In our sample, 55% of women listed casual sex as motivation, while 80% of men did. A Chi-square analysis showed a non-significant result, 2 (1, N=45) =3.24, p=0.072, which suggests that men and women have proportional distributions for their motivation. However, it is expected that increasing the sample size would result in a significant test since the obtained p-value was approaching 0.05 (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Proportion of online dating users interested in “casual sex” as a function of biological sex. More males compared to females indicated this motivation for using online dating apps but is only marginally significant (p=0.072).

Usage and satisfaction

Our data suggest that more college-aged men disproportionately used dating apps compared to women in the last 12 months. There is a possibility that women might report lower satisfaction ratings that could lead to potentially stopping the use of dating apps. Thus, we tested the possibility that there would be sex differences in satisfaction for using dating apps. An independent-samples t-test was conducted to see if there were differences between men (M = 5.04, SD = 2.19, n = 25) and women (M = 5.50, SD = 2.89, n = 20) in their satisfaction for using dating apps. Results show no significant difference, t (43) = 0.547, n.s.

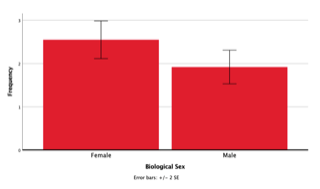

Remarkably, while there seems to be more men who use dating apps and sites, it has been reported that the majority of men do not receive what they deem to be enough messages from dating sites, which might lead to a lower rate of satisfaction (Anderson, Vogels & Turner, 2020). This might be true for our sample as well. We tested sex differences in the number of times our participants checked the dating app within one week using an independent-samples t-test, two-tailed. Results showed that there was a significant difference between men (M = 1.92, SD = 0.91, n = 25) and women (M = 2.55, SD = 1.05, n = 20), t (43) = 2.156, p = 0.037. In our sample, women tended to check their dating apps more often than men, perhaps implying that they check their app more because they get more notifications from responses, relative to men (Figure 3). A previous study from Queen Mary University of London that examined user behavior on the application Tinder within New York City and London, found that women receive matches at a much higher rate than men (10% of the time as compared to 0.6%) (MIT Technology Review 2016). Given this higher rate of matches or perceived success on the app, this could potentially explain why women use the app more frequently. Notably, the interactions from dating apps could be both positive and negative. Negative interactions include continued contact after saying that they were not interested, an unsolicited sexually explicit message or image, being called an offensive name, or a threat of physical harm (Anderson, Vogels & Turner, 2020).

Figure 3: Mean frequency of checking online dating apps as a function of biological sex. Women significantly checked online dating apps compared to men. Error bars +/- SD.

These data, together with the lack of a statistical difference in satisfaction ratings, imply that men and women might have different sources of dissatisfaction with dating apps. As suggested by Pew research, more women reported being targeted by harassment compared to men (Anderson, Vogels & Turner, 2020). It would be interesting to test the factors, such as the perceived danger of dating apps, or the actual experience of harassment, that lead to lower rates of dating app usage in women. Complementarily, the relatively high dating app usage in men is also noteworthy, as they report concerns over a lack of responses and dishonesty from other users.

Previous research has been done regarding the tendency of males to prefer or to be more accepting of casual sex in comparison to women. As previously mentioned, males in our study were more motivated to use the apps to find casual sex than the women in our study. The results for this analysis were marginally significant, but could potentially be significant with a larger sample size. The question of why men and women differ in their attitudes towards casual sex has been a longstanding one. Robert Trivers’ Parental Investment Theory may partially explain this disparity. Part of his theory is that female parental investment is typically higher than male parental investment, and that the sex with more investment will have stronger preferences in regards to who they mate with (Trivers, 1972). Based on this theory, females will be more selective about their partners, possibly limiting the chances for casual sex encounters. The benefits of short term mating are also different for men and women. Speaking in terms of benefits from an evolutionary perspective, to a male, many sexual encounters with many women in a year can lead to the production of multiple offspring, but a woman can only produce one child in the same time period. There does not seem to be much benefit to women to engage in short term sexual encounters. On the contrary, there seems to be more risks associated with casual sex for women than there are for men. Women risk greater damage to their reputation, and losing out on future encounters due to a lower perception of value. Later research by Buss & Schmitt revealed that when asked about their ideal number of sexual partners in a lifetime, the average answer for men was 18, while the average answer for women was around 4.5 (Buss & Schmitt, 1993). This upholds the notion that men prefer casual sex more than women do.

Research conducted on the campus of Florida State University showed that male students were far more likely to be willing to engage in casual sex than their female counterparts. In two studies on the campus, one conducted in 1978 and the other in 1982, students were approached by an experimenter and told that they were attractive, then were asked one of three questions, which were rotated among subjects. The options were a request for a date, an invitation to go back to the experimenter’s apartment, and an invitation to go to bed with the experimenter. In both studies, 0% of females agreed to go to bed, while 75% of males agreed to do so in the 1978 study, and 69% of males in the 1982 study (Clark & Hatfield, 1989).

Given our ever-advancing technological world, our research can be of use to college students as the use of dating apps is quickly becoming an undeniable part of college culture. Since this phenomenon has only emerged in recent years, the waters are still relatively untested, and college students may have many concerns surrounding dating apps. The current study investigated the usage of dating apps in college-aged men and women. Women tended to use dating apps less than men. In those who use the apps, women tend to check their apps more often than men, but there were no statistical differences in satisfaction or motivation between men and women.

Excitement of uncertainty

In general, it seems that the limitation of dating apps is the sense of trust and security from their users as only a subset of users actually meet from using dating apps. Therefore, there might be other factors that might explain the popularity of dating apps. Given that men seem to comprise the majority of users on dating apps, despite generally receiving fewer “matches”, one must wonder why they continue to use the applications if they are not “successful”. Perhaps this means that there are other motivations to use these apps, such as thrill seeking. The behavior appears similar in a way to gambling; app users enjoy the possibility of a match enough to outweigh not receiving as many as they may possibly want.

Despite a lower rate of matches, which would indicate a lower rate of success when compared to women, men still comprise the majority of the user base on dating apps. Why keep using it if it is not working? Similar to gambling, users of these apps may find excitement in the sheer possibility of getting a match, making the experience of using the app enjoyable for them even if they aren’t obtaining any success. They may keep using these apps because they feel that they are bound to have success at a certain point, similar to patrons of a casino who spend all night at the roulette table, but with no wins. Aside from the thrill of potential success, it is possible that men are staying on these apps simply because it is deemed “the thing” to do. Perhaps male college students know that many of their fellow classmates are on these apps, so they feel compelled to use them as well. Technology and social interaction have become increasingly integrated with one another, to a point where many connections nowadays are made online, oftentimes via dating apps (Stevens & Morris, 2007). Humans are highly social beings, constantly seeking connections with other humans. Maybe at the root of the desire to use these apps is the intrinsic longing for human connection, a powerful inclination that keeps people using dating apps, no matter the outcome that the user experiences.

Limitations of the study

Some limitations did arise during this research. Given that the sample was derived from one college campus, the results may not accurately reflect the trends and behaviors of all college students. Collecting data from one campus also skewed the demographics of this study. There were a disproportionate number of responses from white students, with few minority students being included in the sample. This could be attributed to the racial composition of the University of South Carolina’s Columbia campus, where this data was collected. University of South Carolina’s Columbia campus’ undergraduate enrollment is comprised of 76.7% white students, 10.2% African American students, 0.2% Native American students, 2.3% Asian students, 4.0% Hispanic students, 0.1% Pacific Islander students, and 3.2% multiracial students, according to the University of South Carolina Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. This page also includes 1.6% NR Alien and 1.7% No Response undergraduate students on the Columbia campus, two groups that were not included in our sample (University of South Carolina Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion, n.d.). Besides the campus being predominantly white undergraduate students, the small sample size does not reflect the diversity of campus.

Future directions

Further research can be done on this topic, ideally with a larger sample size, and a more diverse sample. Another interesting factor that could be examined in future studies is how a person’s sexual orientation affects dating app usage, something that was not examined in this study. Since this study collected data from those who have used dating apps, it may be the case that there were some students in our sample who tried dating apps, were dissatisfied with them, and stopped their usage. This may have skewed our sample in potentially making it more likely that people in our sample were satisfied. It would be interesting to conduct further research on this topic, perhaps in a more controlled nature. A possible future direction for research on this topic would be to have a number of single people download one or more apps and have the participants use these apps for a certain period of time while tracking their satisfaction with the app. This type of study provides the opportunity for a potentially more accurate satisfaction rating. Another interesting direction for a future study would be to conduct the study across various college campuses around the country. This would give a greater sense of trends and behaviors applicable to the population of college students as a whole, while also allowing the study of trends by geographical region and institution type (e.g. user behavior at state schools versus private universities).

About the Author

Emma Doyle

Emma Doyle

My name is Emma Doyle, and I am a senior Psychology major with a Spanish minor from Long Island, New York. Post graduation I plan on attending graduate school to earn a PhD. in School Psychology. This topic was of interest to me because during my time at Carolina I have observed the popularity of dating apps among my fellow students. The phenomenon of online dating is also relatively new, so I was interested in contributing to a growing body of research. Working on this project has helped make me a better scholar, as it has deepened my understanding of the process of data collection, academic writing, and statistical analyses.

I would like to thank several people for the important roles that they played in this project. This research was originally done as part of the final project for my course section of Laboratory in Psychology. I wish to thank both my laboratory partner, Katerina Delidakis, as well as Jonathan Rann, who was the teaching assistant for my section of that class. I also wish to thank Dr. Melanie Palomares, my professor for Laboratory in Psychology. Aside from teaching me about statistics and the process of scientific writing, Dr. Palomares has been a great mentor to me during the process of finalizing this paper for publication, enhancing both my understanding for and love of academia. Lastly, I thank all participants of this study for their role in advancing the scientific body of work.

References

Alexopoulos, C., Timmermans, E., & McNallie, J. (2020). Swiping more, committing less: Unraveling the links among dating app use, dating app success, and intention to commit infidelity. Computers in Human Behavior, 102, 172–180. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.08.009

Alter, C. (2015, May 15). Whitney Wolfe Wants to Beat Tinder at Its Own Game. Time. https://time.com/3851583/bumble-whitney-wolfe/

Anderson, Vogels, and Turner. (2020, February 6). The Virtues and Downsides of Online Dating. Pew Research Center. https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2020/02/06/the-virtues-and-downsides-of-online-dating/&sa=D&ust=1598990741100000&usg=AFQjCNHYtw-QpBvkEz2TK7G0rpfZuLu3Eg

Buss, D. M., & Schmitt, D. P. (1993). Sexual Strategies Theory: An evolutionary perspective on human mating. Psychological Review, 100(2), 204–232. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295x.100.2.204

Carman, A. (2019, April 9). Hinge’s redesign is all about wanting you to eventually delete the dating app. The Verge. https://www.theverge.com/2019/4/9/18297278/hinge-designed-to-be-deleted-dating-app-redesign

CBS News. (2020, July 22). Hackers expose first Ashley Madison users. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/hackers-expose-first-ashley-madison-users/

Chan, L. S. (2017). Who uses dating apps? Exploring the relationships among trust, sensation-seeking, smartphone use, and the intent to use dating apps based on the Integrative Model. Computers in Human Behavior, 72, 246–258. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.02.053

Clark, R., & Hatfield, E. (1989). Gender Differences in Receptivity to Sexual Offers. Journal of Psychology & Human Sexuality, 2(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1300/j056v02n01_04

Clement. (2020a, July 16). Most popular dating apps in the United States as of September 2019, by audience size. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/826778/most-popular-dating-apps-by-audience-size-usa/

Clement. (2020, July 16). Most popular dating apps in the United States as of September 2019, by audience size. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/826778/most-popular-dating-apps-by-audience-size-usa/

Dye. (2016). The Effects of Technology on College Life. Scholar Commons, 1–6. https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/senior_theses/119

McAlone. (2016, June 2). These are the dating apps that have the highest percentage of women. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/dating-apps-that-have-highest-percentage-of-women-2016-6?international=true&r=US&IR=T

MIT Technology Review. (2016, July 15). How Tinder “Feedback Loop” Forces Men and Women into Extreme Strategies. https://www.technologyreview.com/s/601909/how-tinder-feedback-loop-forces-men-and-women-into-extreme-strategies/

Reimann. (2016, September 22). The chatty, charming history of personal ads. Timeline. https://timeline.com/tinder-personal-ads-history-4c34c7d6dbcb

Stevens, S. B., & Morris, T. L. (2007). College Dating and Social Anxiety: Using the Internet as a Means of Connecting to Others. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(5), 680–688. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.9970

Sumter, S. R., Vandenbosch, L., & Ligtenberg, L. (2017). Love me Tinder: Untangling emerging adults’ motivations for using the dating application Tinder. Telematics and Informatics, 34(1), 67–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2016.04.009

Trivers, R. (1972). Sexual Selection and the Descent of Man: The Darwinian Pivot. Chicago, United States of America: Transaction Publishers.

University of South Carolina Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. (n.d.). Demographics - Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion | University of South Carolina. Retrieved from https://www.sc.edu/about/offices_and_divisions/diversity_equity_and_inclusion/diversity_data/demographics/index.php

Vedantam, R. (2020, February 14). Which Dating Apps are reigning in the USA? App Ape. https://en.lab.appa.pe/2020-02/which-dating-apps-are-reigning-in-the-usa.html