AUTHOR

McNamee, Anna

MENTOR

Heather Peterson

Abstract

This paper examines advertisements for patent medicines and nostrums, from the Colonial Period to the Food and Drug Act of 1906. The Pure Food and Drug Act represented the triumph of the medical profession over state legislation and unsupervised patent medicine manufacturing. Tracing these advertisements alongside the historiography of science, medicine, and advertising; this paper argues that advertisements for patent medicine represent a shift in the culture of healing and the growth of medical knowledge in the United States. By the end of the nineteenth century, science and medicine made great advances and medical professionals began influencing both state and popular opinion. Likewise, the growth of the press highlighted both the successes of modern medicine and the quackery of so-called “cure-alls.” These advertisements reflect these transitions and serve as a window into popular ideas surrounding healing and authority.

Changes in Medical Knowledge and Patent Medicine

Patent medicines, also called nostrums, were an important part of most American families’ medicine cabinets for two hundred years and advertisements for these products reflect advances in science and the creation of the modern medical market.[1] While advertisements call their products “patent medicines,” these cures were usually over-the-counter drugs available without a doctor’s prescription. In the period between 1745 and 1910 advertisements promised a variety of cures. As we see in this advertisement for Medicated Oil Silk, patent medicines offered expansive hope: “Humanity requires [Dr. Morange’s Medicated Oil Silk] to proclaim to the public an exterior remedy for the cure of all disorders.”[2] During the Colonial period patent medicines were imported from England and governed by English patent law. In England, royalty gave out patents through an official document, which established new items for trade creating monopolies. During this period, advertisements for patent medicines reflected a larger cultural and scientific fixation on the metropole.[3] London was the center for scientific innovation through the exchange of information, medicine, and specimens. After the Revolutionary War, the new nation created its system of patents, even though few of these cures were actually patented, and American-made patent medicines took off. The popularity of these cures drove the American medical practitioners to search for authority in medical cures and scientific truth not based on British medical traditions. The phrase patent medicine inspired confidence in the consumer about the quality of the product because it implied some type of government oversight and regulations. Over time, the public became disillusioned by these advertising pitches as national newspapers began to publish stories about frauds. Patent Medicine advertisements represent a shift in the culture of healing and the growth of medical knowledge and state regulations in the United States.

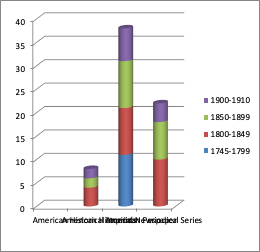

The advertisements from the patent medicine era used in this paper were from three

different academic databases. These databases were: American Historical Imprints, American Historical Newspaper, and the American Periodical Series. The databases contained patent medicine advertisements from 1745 through 1910.

With a total of 64 advertisements compiled, over half of these come from the American Historical Newspaper database, as shown in the graphic. This graphic also shows the number of advertisements

from each period. These newspaper advertisements were from all over the United States

but the majority of them were from New York, Ohio, Michigan, Maine, and Pittsburg.

Examinations of each source show that they contain the entire advertisement and not

just a sampling or summary. After reviewing all 64 sources, the advertisements cited

in this paper best illustrate each time period’s advertising and print techniques.

The advertisements from the patent medicine era used in this paper were from three

different academic databases. These databases were: American Historical Imprints, American Historical Newspaper, and the American Periodical Series. The databases contained patent medicine advertisements from 1745 through 1910.

With a total of 64 advertisements compiled, over half of these come from the American Historical Newspaper database, as shown in the graphic. This graphic also shows the number of advertisements

from each period. These newspaper advertisements were from all over the United States

but the majority of them were from New York, Ohio, Michigan, Maine, and Pittsburg.

Examinations of each source show that they contain the entire advertisement and not

just a sampling or summary. After reviewing all 64 sources, the advertisements cited

in this paper best illustrate each time period’s advertising and print techniques.

Eighteenth Century Imported Patent Medicines and Medical Practices

America’s natural resources and scientific specimens were integral to the promotions made by English writers, causing London to become the global center for scientific learning.[4] During the colonial period, the colonists’ believed that the environment had the power to alter their minds and bodies.[5] The English understood that the natural world, according to the classic Humoral teachings, would affect them. This belief illustrated that “Nature was thus not only understood as a potential stock of resources or a plot of property or as a new location of an old drama between God and humanity; it was also breathed in, drunk, eaten, absorbed under the skin, and incorporated into one’s faculties.”[6] Susan Parrish notes in her examination of the colonies that when European, Native American, and African traditions met; it created a science, driven by curiosity about nature. Women were particularly valued as important gatherers of medical knowledge because of their understanding of the natural world through their love of colors, textures, and small objects; such as shells and flowers.[7] The Native Americans were in this pursuit because of their association with a hidden nature, which “led the colonials on one hand provisionally to trust Indians as both collectors of and testifiers about flora, fauna, and topography of North America.”[8] The Europeans viewed Africans as potentially dangerous and cunning because of their familiarity with poisonous plants and antidotes.

Correspondence between the metropole (Britain) and the periphery (the colonies) was characterized by letters, pictures, and engravings. For example, Hezekiah Usher’s engravings of the Moffet’s great yellow and black Virginia butterfly enabled natural scientists in London to “remedy the colonists’ seclusion and ignorance.”[9] Because colonists lived a great distance from their English correspondents, they used physical objects to portray natural science. A letter and a physical specimen characterized most of the transfer of knowledge between England and the colonists.[10] While marginalized people groups in the New World had a particular form of agency and authority in natural science; the connection was through people, specimens, and letters. However, London was still promoted as the center for scientific activity; both the English and the colonists envisioned a “lateral” relation, which enabled England to receive the specimens and letters from the best observers in the colonies.[11]

English patent medicines originally referred to medicine with ingredients granted protection by the government for exclusivity. English patents had a fourteen-year restriction period. This system allowed the patent holder to have a monopoly over their particular product.[12] Having a medicine patented gave others the inability to copy the design of the bottle or ingredients. The American patent system styled the same procedures as the English patents. American Patent medicine manufacturers usually used this system to patent the bottle and labels. In reality, this process did little to stop forgeries and many prominent nostrum manufacturers ended up changing their bottle and ingredient designs. According to James Harvey Young, the first forgeries of patent medicine began in the 1790’s when Samuel Lee Jr. secured the first patent for his Bilious Pills. Three years later, Samuel H. P. Lee began to sell a medicine under the same name.[13] While British patents held weight among the public due to the long history with England and their monopoly patents, the colonial system did not provide any government oversight to make sure that unpatented material was not sold on the market or to prevent others from stealing patented remedies. Because the American people were already familiar with British medicines, advertisers used the medicinal brands transported from England to appeal to their audiences through distinctive names and packaging. For example, Dalby’s Carminative from Wellbeck-Street London used this technique by mentioning how this medicine from his, “Apothecary […] ha[s] long been e[s]table[s]hed a[s] a most [s]afe and effectual remedy.”[14] This technique allows the manufacturer to make a persuasive argument, especially to parents with an infant, “afflicted with wind cholics, convul[s]ions, dry gripes, and all tho[s]e in the [s]tomach and bowel[s],” to trust this remedy, because it is a recognized and reputable brand.[15] Eighteenth-century patent medicines usually stated that they were London imported. The Royal Patent Medical Chewing Tobacco assured purchasers that this tobacco was “truly imported from their original ware-hou[s]e[s] in London.”[16] Even though tobacco was not grown in London, the manufacturer uses the name and the emphasis placed on the product as “royally patented” to show that England dominated the medicine market by using the familiarity of these products to increase sales. The familiarity used also illustrates that patenting meant something to the consumer, who trusted the patent.

During the end of the eighteenth century, many physicians still used the Humoral system; however, there was also a great deal of scientific innovation. Dr. David Hosack, who was an educated physician, did not agree with the technique of bloodletting. He argued that bleeding a patient took away the energy required by the body to fight a fever. Hosack believed the trick was to help the patient sweat out the fever by stimulating circulation. His patients began to gradually get better under these treatments because it did not, “weaken a patient with blood loss just as their internal organs were threatened with collapse.”[17] Surgery was another medical technique that was controversial among a variety of physicians; however certain physicians thought that it was useful and beneficial in some cases. Surgery had many complications and sometimes caused the patient to die. During the early nineteenth century, physicians like Hosack pioneered innovative surgeries.[18] Medical Botany would eventually create cures that were more effective than patent medicine. The different cures for a patient in the early nineteenth century did not exclude patent medicines. For example, Dr.Hosack notes that he prepared an essential oil “stocked in British Medical shops.” He also used other Hippo-Galenic Old World cures to balance the humours; such as figs, a warm poultice to soothe infected flesh, and sweet bay as a stimulant for “sluggish circulation.”[19] Early American medicine and science looked toward the long-established traditions of Humoral medicine, but patent medicine still enjoyed popularity.

Early American Patent Medicine

The Revolutionary War allowed American manufacturers to replace the old system of British patent medicines and sell them to all of Europe, not just Britain.[20] While many medicines were not patented, the label patent medicine remained a popular term for privately owned drugs, to convey a sense of scientific innovation.[21] For example, Swaim’s Panacea was an incredibly popular medicine during the nineteenth century. Swaim had acquired a patent for his remedy, publishing a list and acknowledged several of the ingredients the remedy contained, while also managing to hint that there were a couple of ingredients kept secret.[22] Swaim also used the formula for Sarsaparilla syrup published in the first edition of the Pharmacopoeia of the United States. His use of the current ideas on natural medical drugs made his remedies both instantly appealing to doctors and the poor.[23] Many manufacturers of medicine appealed to their consumers through fake medical degrees, such as Dr. Swaim who claimed to have twelve degrees, because this link with credentials to a physician’s dedication to healing provided confidence in the product.[24] This is evident in almost all of the collected patent medicine advertisements, as they either claim to have a medical degree or have reviews from doctors who were cured and recommend these cure-all remedies.

Patent medicines were cheap and easy to obtain. These medicines were not only sold to doctors, but customers could buy chests filled with bottles of common remedies.[25] The ability to purchase medication to cure an ailment rather than see a doctor made patent medicines popular. Consumers were wary of doctors since they sometimes liked to use cures that had harsh chemicals, such as mercury which doctors used as a purgative and for treating fevers.[26] Allopathic treatments were known to be especially harsh, which pushed patients to seek other alternative healing methods through homeopathy and patent medicine. For example, the standard Allopathic treatments for Cholera consisted of bloodletting, calomel, chloroform, opium, emetics, sedative “anti-spasmodics,” saline, brandy and laudanum, hot milk and brandy, and wearing wool.[27] Patent medicines also appealed to consumers as it was much easier and far cheaper to purchase a patent medicine than to see a doctor because physicians needed payment for each mile and must receive a monetary payment.[28] People who lived in rural Charlottesville, Virginia, paid three dollars to see a doctor if they were a mile outside of the doctor’s designated area and thirty-three cents per mile after.[29] Patent medicines were not only sold to doctors, during the early eighteenth century, “but also many other[s] […] who kept medicines on hand at home […] Customer could ask for a particular medicine, or they could buy a portable medicine chest filled with bottles of common remedies.”[30] The ability to purchase medication to cure an ailment rather than see a doctor made it more convenient because the consumer could buy all the medicine they needed in one chest rather than try the physician’s risky procedures.[31]

Mid-Eighteenth Century Advertisements

Advertisements from the mid to late eighteenth century show treatments for generic, all-purpose remedies.[32] Evidence of these generic treatments occurred in almost all advertisements from the 1750’s through the nineteenth and early twentieth century. For example, a 1764 advertisement showed this specificity through the promotion of an Oriental Balsam that prevented apoplexy and sudden death, and “a [s]pecific [cure] for all tho[s]e di[s]order[s] which ri[s]e in the autumn [s]ea[s]on.”[33] This advertisement illustrates the prevalence of the Hippo-Galenic Humoural system, which was prevalent throughout the eighteenth century and states that nature could affect the physical body. This advertisement showed how ambiguous the cure was by the fact that it did not list the specific type of illness this remedy treated, although autumn was frequently associated with melancholy. It is also notable that the advertisement differentiated the drug as Oriental Balsam to distinguish it from American varietals. The manufacturer was purposefully vague about where the cure originated from, simply saying, “Thi[s] Cordial Medicine for age[s], ha[s] been held in the highe[s]t e[s]teem over the whole Ea[s]tern World.”[34] However, it was then processed in London and exported to America. These generic, all-purpose cures were an important technique for patent medicine advertising because it made that remedy the only one that a person will ever need.

These advertisements attest to the naiveté of readers, who might believe that these tinctures could magically cure them. Dr. Attridge’s Tincture for Dyspepsia claims that “thousands are lingering under this disease in some form, sinking into the grave without a remedy, whom this medicine would certainly restore to perfect health and vigor.”[35] The advertised remedy promised a swift cure that had no chance of failure. Morange’s Medicated Oil Silk made similar promises that this external remedy could, “cure all chronic disorders.”[36] These likely non-patented remedies were used to cure a variety of illnesses, even though there was no proof that these medicines were effective. The average person might take the cure, and should they recover, the credit was often given to the patented medication. According to Young, natures healing power was the manufacturer’s ally, and should the patient not recover there was no way the patient could tell anyone or disprove the remedy’s effectiveness.[37]

Many advertisements also appealed to consumers through price accommodations for customers who might not otherwise be able to afford the medicine. Five out of the eleven patent medicine advertisements, during this period, showed a willingness to negotiate the price of the medicine for those who had trouble paying. For example, one advertisement stated; “the poor, who are not able to pay for [the secret medicine], may have it gratis.”[38] This advertisement uses this technique by giving this remedy for free to individuals who cannot pay to appeal to their audience. This technique occurs again in 1790, in an advertisement from Doctor Audirac. Doctor Audirac promotes an “incomparable” elixir that was “very nece[ss]ary to be kept in all familie[s].”[39] At the end of the advertisement, he assures the buyer that if need be; the doctor could accommodate price and lodging.

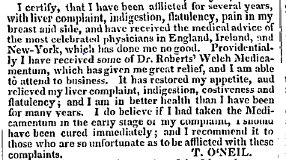

Another technique used in advertisements were testimonials from those who claimed to be afflicted and cured of the disease. An example of a testimony is shown in the photo below.

(Example from the Western Recorder.)[40]

Promoters of patent medicine often sought to establish a sense of trustworthiness by using circumstantial case histories, either real or fictional through a gratitude-filled testimony in the tone of humble citizens. Dr. Robert’s Welch Medicamentum has several testimonies by citizens who “have been affected for years” or someone who “placed little confidence in nostrums or specifics.”[41] Much like Dr. Robert’s endorsement, Dr. Howard’s Vegetable Medicine advertisement includes a very similar testimony.[42] These testimonies tried to add some level of trustworthiness for the consumer on the benefits of the product, in a time where it was impossible to know what was in these remedies and if they actually worked.

The advertisements from this period reflect the growing respect for science and medical degrees, even though the claims seem a bit ridiculous today. Dr. Boozle’s Vegetable Pills used this technique through the claim that he graduated from twelve medical colleges and spent forty years perfecting his remedy.[43] Dr. Attridge’s advertisement claimed there was not a single more important remedy created than his tincture, attributing it to a great scientific advancement.[44] This technique also occurs in an advertisement for Marshall’s Ambrosia, which claimed that never before has there been a better medicine or cure for those, “who have not been, nor can be cured by ordinary medical practice.”[45] Many manufacturers of medicine often claimed in their advertisements that their remedy was the height of scientific discovery and that there was not a medication out with the same powerful cure.

Late Nineteenth Century Advertisements and Medical Advancements

During the latter half of the nineteenth century, medicine and science experienced huge advancements. Doctors began to realize the importance of sanitation when performing procedures and they also began using anesthesia.[46] The developments of the microscope and the ability to understand cells enabled scientists and medical professionals to know more about the human body. A prominent scientist, Rudolf Virchow linked how this new knowledge of cells could affect medicine and disease.[47] The new scientific ability to find the cause of diseases by using the microscope and mapping out areas of cases led governments to realize that an organized systematic approach to treating diseases was possible. This systematic approach is evident in both the 1831 cholera outbreak and the 1853 yellow fever outbreaks and identified a need for public health.[48] Researchers started developing vaccines during this period for Anthrax, Cowpox, and Rabies, which helped the public realize, although not without controversy, that medicine could now cure diseases effectively without harm to the patient. Medicine and medical practices now allowed new cures, through a new understanding of the human body, which now provided more relief than patent medicine or other alternative medical practices.

Medical care achieved significant advancements due to the establishment of legitimate and educated doctors.[49] During the nineteenth century, patients had many conflicting choices for medical care, as there were three different types of medical professionals and treatment: Allopathy, Osteopathy, and Homeopathy. Most doctors gained experience though apprenticeship for three years and a diploma from a physician counted as a degree in medicine. During this period, some medical schools emerged and replaced apprenticeship with two years of study at a medical university. The system of becoming a doctor was not as strict as modern-day practices, which enabled forgeries of medical degrees and allowed those without a medical degree to start medical colleges. The Allopaths and Homeopaths considered themselves rivals with the other, even though neither group had any superior medical knowledge.[50] However, Allopathic doctors used various disease outbreaks to secure their position in health care, and push homeopathic practices and patent medicines off of the market by creating the organization of the American Medical Association.[51] After the creation of the American Medical Association, Allopathic medicine attempted to combat quackery by establishing a distinction between legitimate and educated medical practitioners and uneducated imposters.[52] Also, this distinction between educated medical professionals helped push midwives out of the medical field. Allopathic medical practitioners began to link homeopathy with quackery and argued that homeopathic medicine was not interested in curing diseases but “to dupe urban elites into paying exorbitant sums for their false therapeutics.”[53] Allopaths claimed that the only way anyone accepted the “outdated rationalism” of homeopathy was “for the sake of money.”[54] As a result of this link to quackery, the homeopathic medical practitioners had ignorant and ignoble motives. The link of patent medicine and homeopathic medicine to quackery caused these medical options to be considered outside legitimate medical knowledge.

While medical care became more distinct, changes in American patent law made acquiring a patent difficult for these remedies, making it uninteresting to manufacturers. In 1836, the United States enacted several important changes in patent law, making it harder to obtain a patent. The previous laws did not require evidence of effectiveness and originality of the invention. Required disclosure of ingredients or formulas deterred many manufacturers from patenting the medicine itself.[55] Instead, manufacturers patented the bottle design and copyrighted the labels, promoting posters or advertisements, and the medicinal literature around the bottle.[56] In 1843 a major court case, Wheaton V. Peters, helped to further establish infringement rights for patented items. This case decided what was copyrighted and anything that did not fall under these requirements was free to use. These changes in patent law were exploited by patent medicine manufacturers in their advertisements, to try to limit forgeries.

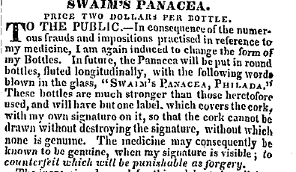

(Example from Western Recorder)[57]

Dr. Chamber’s remedy for Intemperance used the rise of fraudulent patent medicines as a way to scare the public against counterfeits, while also informing them of the new package and bottle design so that an individual can recognize this brand.[58] In addition, Audler’s Asiatic Lenitive for Pain also gives a warning during his ad that none of the medication was “genuine but those signed and sealed patent on the boxes by the patentee.”[59] This same technique was also used in an advertisement of Swaim’s Panacea where the manufacturer informs the public of the new packaging of this remedy so that it can be easily recognizable. Because of the numerous forgeries, “and impositions practices in reference to my medicine, I am again induced to change the form of the Bottle […] with the following words ‘Swaim’s Panacea Philada” […] and will have but one label, which covers the cord, with my own signature on it [... and] contains neither mercury nor any other deleterious drug.”[60] Patent medicine advertisers used the fear of counterfeits to scare the public into buying their particular brand. This tactic; however, seems to draw the consumer’s attention to the possibilities of harsh chemicals within remedies that might be fake.

Patent medicine advertising changed with the times. During the nineteenth century, productivity and faster transportation enabled national-scale businesses to create national brand name products, advertising, and the infrastructure for distribution. Illustrations began to appear commonly in newspapers and magazines during the 1870’s because of new and improved processes in zinc engraving through “the halftone reproduction of lithographs and other graphics,” which increased the quality and speed of producing these illustrations.[61]

Advancements in technology made it much easier for newspapers, advertisements, and magazines to produce illustrations in their material.

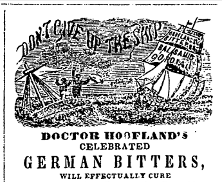

(Example from the Plattsburg Republican)[62]

During the late nineteenth century, pictures began to appear. Ayer’s Sarsaparilla showed a picture of a medicine bottle on the top left corner of the advertisements.[63] This image showed the distinct bottle and label that he had patented so that anyone who saw his advertisement knew to trust this medicine. It was very common during the nineteenth century to patent both the bottle and label, but not the actual medicine. This kept medicine manufacturers from having people steal their bottle design and name so that they did not have a problem with others making counterfeit medicine. Usually, the medicine inside was unpatented because in order to get a patent they had to give up the secret ingredients to their remedy. The drawings in the advertisements were usually very small and only occurred in eight out of thirty advertisements during this time period. Some used biblical depictions, crests, or a mortar and pestle.

New printing technology also allowed for specific dosages and methods of administration. Out of the thirty advertisements, fifteen focus on what dosage the consumer should take for specific symptoms. Ten of them stated that the medicine had a different potency depending on the time of day. An advertisement from Mr. Kennedy of Roxberry gave these specific dosages. He claimed that “two bottles are warranted to cure the worst canker in the mouth and stomach,” while one bottle will cure “these who are subject to a sick headache.”[64] The ability to give all of these instructions was mostly due to the longer length of these advertisements compared to earlier advertisements. Another example of information about these medicines was Ayer’s Cathartic Pills which can be “used in any quantity.”[65] Instructions on how to administer these medicines created a level of trust in the consumer because it was very similar to the way doctors prescribed different cures.[66] The more exact instructions inspired confidence through a belief that the medicine does work and that it will certainly work quickly and efficiently based on the dosage prescribed. In addition, these advertisements suggested that the consumer did not need a doctor to cure them.[67]

Despite the fact that medicine began to improve, patent medicines advertisements often called the medical profession into question, suggesting that their products were safer. Several articles from James Harvey Young, a historian who has heavily researched patent medicines, provides insight into the way the American public viewed mid to late nineteenth-century medicine. The manufacturers promised that there were no harsh chemicals, such as mercury in their formulas.[68] Many advertisements condemned physician’s expensive fees and barbaric methods. The nostrum manufacturers painted doctors as heartless brutes “armed with scalpels and mercurial purges.”[69] Patent medicine manufacturers often portrayed their remedy as an alternative to surgery or any doctors visit. This portrayal of the patent medicine as an alternative to medical treatment occurs in another advertisement for Swaim’s Panacea, it states that this remedy was so effective that it was, “an operation so long looked for in vain of the medical world.”[70] Surgery was no longer required as a cure for the multitude of diseases that this nostrum could heal; a single bottle was supposedly able to outperform nineteenth-century medical practices.

As the newspaper rapidly expanded across the country, consumers were able to express their dissatisfaction with patent medicine cures. The author of the advertisement against patent medicine, “Poisonous Pills For Poor People,” attempted to use his advertisement to warn readers, “of ‘remedies’ that kill rather than cure.”[71] The writer of the article brought attention to the fact that these remedies were either ineffective for curing illnesses, or that they contained the harsh chemicals that consumers tried to avoid. This article also shows that members of the public recognized the ineffectiveness of patent medicine. Also, another advertisement written by a consumer warns against the dangers of patent medicine by claiming he was deceived by medicine advertisements and that others should be wary.[72] Another article published about the ineffectiveness of patent medicine describes the medicine of Dr. S. P. Townsend. This writer informs the public that S. P Townsend, “is not doctor, and never was, is no chemist, no pharmacoutist—knows no more about medicine than or disease than any common man.”[73] This advertisement is another example of the way print enabled consumers to share information about these different remedies. Others should be wary of any medicine made by Dr. S. P. Townsend because he does not have the qualifications to make medicine and his cures are ineffective.

Pure Food and Drug Act and the End of Patent Medicine

The public outrage over the condition of a meatpacking facility featured in Upton Sinclair’s book, The Jungle, led to the comprehensive food and drug law. Afterward, Congress then began to work on legislation “[t]hat it shall be unlawful for any person to manufacture within any Territory […] any article of food or drug which is adulterated or misbranded, within the meaning of this Act.”[74] In 1906, the federal Pure Food and Drug Act tried to eliminate the most prevalent issues in both processed food and patent medicine.[75] Under the new laws, drugs that contained ingredients deemed addictive or dangerous must have their ingredients listed on a product label. The final major revision of the Pure Food and Drug Act by the Food and Drug Administration occurred in 1938 in order to make sure that these products were safe and effective.

Advertisements after the Pure Food and Drug Act turned away from the term patent medicine. Medicine advertisements were no longer associating with the addictive or dangerous ingredients that the government said must be listed on the label. An example of this type of language shift was through the phrase, “[r]emember Father John’s medicine is not a patent medicine, but the prescription of the eminent specialist.”[76] As patenting now became associated with labeling addictive ingredients, Father John’s distanced itself from the term, while simultaneously playing into older tropes of specialization. Another shift can be seen in an advertisement for nervous dyspepsia or indigestion, which played into the public’s growing awareness of diseases as well as a distancing from the term patent medicine. The advertisement notes that “the manufacturers of patent medicine, as a rule, seemed to think their medicines would not sell unless they claim it will cure everything under the sun.”[77]

While the popularity of patent medicines in the colonial period signified a growing trust in state oversight, these regulations eventually spelled the end of patent medicine. Popularity is mostly due to the uncertain and somewhat dangerous procedures used by medical professionals during this time period. As medical treatments became more effective, the public began to distrust patent medicine. Allopathic doctors worked hard to distance themselves from these cures and the formation of the American Medical Association gave doctors a public pulpit. In addition, improvements in preventing diseases through vaccines and a better understanding of the human body revitalized the public’s trust in American medicine. The American Medical Association and the press maligned patent medicine’s unregulated qualities, which led the public to feel that more government supervision and regulations were necessary. The Pure Food and Drug Act paved the way to the modern medicine market through regulated drug ingredients and research into the effectiveness of the medication. Advertisements of patent medicine illustrate and take advantage of the uncertainty of medical practices and cures. Patent medicine is a topic that has not received much attention from historians. Manufacturers of patent medicines used print as a way to market and sell their products by utilizing the widespread reach of newspapers and magazines. An interesting future topic is to discover how the evolution of print, during these periods, plays a role in how manufacturers market their products.

About the Author

Anna McNamee

Anna McNamee

My name is Anna McNamee and I am from Aiken, South Carolina. I just recently graduated in May of 2019 from the University of South Carolina-Aiken majoring in both English and history with a minor in music. This year I received an award as the outstanding student in history for 2018-2019. My motivation for writing this paper stemmed from my interest in American history and medicine. This project has taught me to research and collect primary sources and find good secondary historical literature in a variety of subjects. The work I have done on this paper throughout the semester will enhance my ability to collect and synthesize information and think critically, which I will utilize in the workplace. I want to thank my mentor Dr. Heather Peterson for helping me this semester. In addition, I would also like to thank Dr. Elizabeth Georgian, who gave me the idea for this topic.

Resources

[1] For this paper the term patent medicine will describe medicines that were both patented and non-patented.

[2]“Advertisement 6 – No Title,” Western Recorder (1824-1833), Aug. 23, 1825.

[3] Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World (University of North Carolina Press, 2006), 25.

[4] Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity, 25.

[5]Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity, 77.

[6] Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity, 78.

[7] Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity, 314.

[8] Kelly Wisecup, Medical Encounters: Knowledge and Identity in Early American Literatures (University of Massachusetts Press, 2013).

[9] Susan Scott Parrish. American Curiosity, 111.

[10]Kelly Wisecup, Medical Encounters: Knowledge and Identity in Early American Literatures, 107.

[11] Susan Scott Parrish, American Curiosity, 88.

[12]Lori Loeb, "Doctors and Patent Medicines in Modern Britain: Professionalism and Consumerism," Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies 33, no. 3 (2001): 404-25.

[13]James Harvey Young, "Patent Medicines: An Early Example of Competitive Marketing," The Journal of Economic History 20, no. 4 (1960): 648-56.

[14] “Advertisement 3—No Title,” The New-York Morning Post, And Daily Advertiser, July 14, 1785.

[15] “Advertisement 3—No Title,” The New York Morning Post, And Daily Advertiser. July 14, 1785.

[16] “Advertisement 4—No Title,” Pennsylvania Gazette, no. 1384. July 7, 1755. 3.

[17] Victoria Johnson, American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic (Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2018).

[18] Victoria Johnson, American Eden, 195.

[19] Victoria Johnson, American Eden, 314.

[20]James Harvey Young, "Patent Medicines: An Early Example of Competitive Marketing," 680.

[21]Lori Loeb, "Doctors and Patent Medicines in Modern Britain: Professionalism and Consumerism,"408.

[22]James Harvey Young, The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America Before Federal Regulation (Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1972).

[23] James Harvey Young, The Toadstool Millionaires, 61.

[24]Nancy Tomes, "Merchants of Health: Medicine and Consumer Culture in the United States, 1900-1940," The Journal of American History 88, no. 2 (2001): 519-47.

[25] Owen Whooley, Knowledge In The Time of Cholera: The Struggle Over American Medicine In The Nineteenth Century (University of Chicago Press, 2013), 20.

[26] Victoria Johnson, American Eden, 21.

[27] Owen Whooley, Knowledge In The Time Of Cholera, 41-42.

[28]James Harvey Young, "American Medical Quackery in the Age of the Common Man," The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 47, no. 4 (1961): 579-93.

[29] “Agreed Rate of Medical Charges,” University of Virginia, 1848. http://blog.hsl.virginia.edu/feebill/wp-content/uploadvertisements/sites/12/2011/05/Fee-Bill1.jpg

[30] Victoria Johnson American Eden 20.

[31] Victoria Johnson, American Eden, 21.

[32]Robin Myers, Michael Harris, and Giles Mandelbrote, Books for Sale: The Advertising and Promotion of Print Since the Fifteenth Century (New Castle: Oak Knoll Press, 2009), 57.

[33] “Advertisement 37—No Title,” New York Mercury, no. 792. Jan. 5, 1767.

[34] “Advertisement 37—No Title,” New York Mercury.

[35]“Advertisement 5 – No Title," Western Recorder (1824-1833), May 18, 1830.

[36] “Advertisement 6 – No Title,” Western Recorder (1824-1833), Aug. 23, 1825.

[37] James Harvey Young, “Patent Medicines: An Early Example of Competitive Marketing,” 653.

[38] “Advertisement 36—No Title,” Pennsylvania Gazette, no. 1384. July 7, 1755.

[39] “Advertisement 38—No Title,” The Federal Gazette and Philadelphia Dailey Advertiser, no. 8001, April 7, 1790.

[40] “Advertisement 8 – No Title," Western Recorder (1824-1833), Aug 10, 1830.

[41]"Advertisement 8—No Title,” Western Recorder.

[42] Advertisement 9 -- No Title," Western Recorder (1824-1833), May 18, 1830.

[43]"Puck's Exchanges," Puck (1877-1918), Mar. 3, 1880, 850.

[44] “Advertisement 6– No Title." Western Recorder (1824-1833), May 18, 1830.

[45] “Advertisement 7 – No Title," Western Recorder (1824-1833), May 18, 1830.

[46] Owen Whooley, Knowledge In The Time of Cholera, 140.

[47]William F. Bynum, A Little History Of Science (Yale University Press, 2012), 157.

[48] William G. Bynam, A Little History Of Science, 163.

[49] Owen Whooley, Knowledge In The Time of Cholera, 75.

[50] Owen Whooley, Knowledge In The Time of Cholera, 75.

[51] Owen Whooley, Knowledge In The Time Of Cholera, 80.

[52] Owen Whooley, Knowledge In The Time of Cholera, 95.

[53] Owen Whooley, Knowledge In The Time Of Cholera, 99.

[54] Owen Whooley, Knowledge In The Time Of Cholera, 100.

[55] Lori Loeb, “Patent Medicines in Modern Britain,” 409.

[56] James Harvey Young, “Medical Quackery In The Age Of The Common Man,” 587.

[57] "Advertisement 33 -- No Title," Western Recorder (1824-1833), Aug 10, 1830.

[58]“Advertisement 44—No Title,” The Portsmouth Journal and the Rockingham Gazette, 39, no. 3453, June 14, 1828.

[59]Advertisement 43—No Title,” The American, 1, no. 17. Mar. 28, 1820.

[60]"Advertisement 33 -- No Title," Western Recorder (1824-1833), Aug 10, 1830.

[61] Carl F. Kaestle and Janice A. Radway, A History of the Book in America: Volume 4: Print in Motion: The Expansion of Publishing and Reading in the United States, 1880-1940: A History of the Book in America (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009), 13.

[62] “Advertisement 64—No Title,” Plattsburg Republican. 3, Sept. 25, 1858.

[63] “Advertisement 48—No title.” The Farmer’s Cabinet. 76, no. 48, June 4, 1878.

[64]“Advertisement 51—No Title,” The Pittsfield Sun, 105, no. 2833. Jan. 4, 1855.

[65] “Advertisement 49—No Title,” The Farmer’s Cabinet, 77, no. 35. March 4, 1879.

[66] Owen Whooley, Knowledge In The Time of Cholera, 149.

[67]James Harvey Young, “Medical Quackery In The Age Of The Common Man,” 585

[68] James Harvey Young, “Medical Quackery In The Age Of The Common Man,” 580.

[69] James Harvey Young, “Medical Quackery In The Age Of The Common Man,” 580.

[70]“Advertisement 10 -- No Title," Western Recorder (1824-1833), Sep 18, 1857.

[71]“POISONOUS PILLS FOR POOR PEOPLE,” 5.

[72] Charity Shaw. “Indian Medicines,” American Historical Imprints. 1905.

[73] “Advertisement—63 No Title,” Litchfield Republican, Aug. 8, 1850.

[74] Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (sections 301 - 399d).

[75] James Harvey Young, "Food and Drug Regulation under the USDA, 1906-1940," 23.

[76]“Advertisement 61-- No Title.” Baltimore, Maryland, Nov. 8, 1907.

[77]"Advertisement 62 -- No Title." Christian Observer (1840-1910), Nov 09, 1910, 19.

Bibliography

Newspaper Advertisements

“Advertisement 1—No Title.” New-York Morning Post. Jan. 17, 1792.

“Advertisement 2—No Title.” The New-York Morning Post And Daily Advertiser. June 3, 1786.

“Advertisement 3—No Title.” The New-York Morning Post, And Daily Advertiser. July 14, 1785.

“Advertisement 4—No Title.” The New-York Morning Post. July 20, 1784.

“Advertisement 5—No Title.” Columbian Gazette. 10, no. 482. Sept. 6, 1812.

“Advertisement 6—No Title. Virginia Patriot. Sept. 6, 1812

“Advertisement 7—No Title.” Maryland Gazette. no. 1018. Aug 11, 1764, 3.

“Advertisement 8 -- No Title.” Western Recorder (1824-1833). Oct 13, 1829.

"Advertisement 9 -- No Title." Western Recorder (1824-1833). Jan 18, 1831.

“Advertisement 10 -- No Title." Western Recorder (1824-1833). Sep 18, 1827.

“Advertisement 11 -- No Title." Western Recorder (1824-1833). Mar 24, 1829.

“Advertisement 12 -- No Title." Western Recorder (1824-1833). May 18, 1830.

“Advertisement 13 -- No Title." Western Recorder (1824-1833). Jul. 21, 1829.

“Advertisement 14—No Title.” Albany Evening Journal, 6. no. 1764. Dec. 1835.

“Advertisement 15—No Title.” Baltimore Gazette and Daily Advertiser. 84, no. 13995. Dec 22, 1835. 4.

“Advertisement 16 -- No Title.” Christian Secretary (1822-1889). 30. Dec. 12, 1851.

“Advertisement 17 -- No Title." Saturday Evening Post (1839-1885). Oct 07, 1882.

“Advertisement 18 -- No Title.” Michigan Farmer (1843-1908). 51, no. 146. Feb. 9, 1907.

“Advertisement 19 -- No Title.” Michigan Farmer (1843-1908). 49, no. 182. Feb. 24, 1906. “Advertisement 20 -- No Title. Ohio Farmer (1856-1906). 62, no. 220. Oct. 7, 1882.

“A Cheap and Effectual Medicine to Cure the Colera, or Colick. From the Edinburgh Medical Effays, Vol. 5. p. 646.” American Magazine & Historical Chronicle. September 1746.

Shaw, Charity. “Indian Medicines.” American Historical Imprints. 1805.

“Advertisement 23-- No Title.” Christian Secretary (1822-1889). 30, Sept. 12, 1851. 4.

“Advertisement 24 -- No Title.”Bowen's Boston News - Letter, and City Record (1825-1827). Jan. 1927.

“Advertisement 25 -- No Title.” Western Recorder (1824-1833).Oct. 05, 1830.

“Advertisement 26 -- No Title.”Western Recorder (1824-1833). Aug. 23, 1825.

“Advertisement 27 -- No Title.”The Farmer’s Cabinet. Jan. 3, 1840.

“Advertisement 28 -- No Title. Western Recorder (1824-1833). Aug. 28, 1827.

“Advertisement 29 -- No Title." Morning News. June 23, 1847.

“Advertisement 30 -- No Title." Western Recorder (1824-1833). May 01, 1827.

"Advertisement 31-- No Title." Life (1883-1936). Feb 19, 1903.

"Puck's Exchanges." Puck (1877-1918). Mar. 3, 1880.

"Advertisement 33 -- No Title." Western Recorder (1824-1833). Aug 10, 1830.

"Advertisement 34 -- No Title." The Barre Patriot. Dec. 15, 1849.

“Advertisement 36—No Title.” Pennsylvania Gazette. no. 1384. July 7, 1755.

“Advertisement 37—No Title.” New York Mercury. no. 792. Jan. 5, 1767.

“Advertisement 38—No Title.” The Federal Gazette and Philadelphia Dailey Advertiser. no. 8001, April 7, 1790.

“Advertisement 39—No Title.” New-York Daily Gazette. no. 727, April 25, 1791.

“Advertisement 40—No Title.” New Jersey Journal. 15, no. 776, Vol. 15. Aug. 28, 1798.

“Advertisement 41—No Title.” MercantileAdvertiser. no. 3374, June 11, 1803.

“Advertisement 42—No Title.” CommercialAdvertiser. 15, no. 6368. Dec. 21, 1812.

“Advertisement 43—No Title.” The American. 1, no. 17. Mar. 28, 1820.

“Advertisement 44—No Title.” The Portsmouth Journal and the Rockingham Gazette. 39, no. 3453. June 14, 1828.

“Advertisement 45—No Title.” New Hampshire Patriot and State Gazette. 3, no. 133. Dec. 6, 1859.

“Cut This Out” Farmer’s Cabinet. 74, no. 19. Nov. 17, 1875.

“Advertisement 47—No Title.” The Farmer’s Cabinet. 74, no. 29. Jan. 26, 1876.

“Advertisement 48—No Title.” The Farmer’s Cabinet.76, no. 48, June 4, 1878.

“Advertisement 49—No Title.” The Farmer’s Cabinet. 77, no. 35. March 4, 1879.

“Advertisement 50—No Title.” The Farmer’s Cabinet. 53, no. 22. Jan. 4, 1855.

“Advertisement 51—No Title.” The Pittsfield Sun.105, no. 2833. Jan. 4, 1855.

“Advertisement 52—No Title.” The Farmer’s Cabinet. 58, no. 47. June 13, 1860.

“Advertisement 53—No title.” The Farmer’s Cabinet. 65, no. 47. June 13, 1867.

“Advertisement 54—No title.” The Farmer’s Cabinet. 72, no. 47. June 3, 1874.

“Advertisement 55—No title.” Michigan Farmer (1843-1908). 1, no. 56. Feb 09, 1907.

"Advertisement 56 -- No Title." Ohio Farmer (1856-1906). 103, no. 16, Apr 16, 1903.

"Advertisement 57 -- No Title." Maine Farmer (1844-1900). 68, no. 47. Sep 20, 1900.

"Advertisement 58 -- No Title." Health (1900-1913). Jan. 1, 1905.

"Advertisement 59 -- No Title." Life (1883-1936). 57, no. 1486, Apr 20, 1911.

"Advertisement 60 -- No Title." Herald of Gospel Liberty (1808-1930). 103, no. 13, Mar 30, 1911.

Advertisement 61-- No Title.” Baltimore, Maryland, Nov. 8, 1907.

"Advertisement 62 -- No Title." Christian Observer (1840-1910), Nov 09, 1910.

“Advertisement—63 No Title,” Litchfield Republican, Aug. 8, 1850.

“Advertisement 64—No Title,” Plattsburg Republican. 3, Sept. 25, 1858.

“Agreed Rate of Medical Charges.” University of Virginia. 1848.

“POISONOUS PILLS FOR POOR PEOPLE.” Puck (1877-1918), 77, 5. March 13, 1915.

Secondary Sources

Bynum, William F. A Little History In Science. Yale University Press, 2012.

Donohue, Julie. "A History of Drug Advertising: The Evolving Roles of Consumers and Consumer Protection." The Milbank Quarterly 84, no. 4 (2006): 659-99.

Gardner, Jared. The Rise and Fall of Early American Magazine Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2012.

Johnson, Victoria. American Eden: David Hosack, Botany, and Medicine in the Garden of the Early Republic. Liveright Publishing Corporation, 2018.

Kaestle, Carl F., and Janice A. Radway. A History of the Book in America: Volume 4: Print in Motion: The Expansion of Publishing and Reading in the United States, 1880-1940. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2009.

Law, Marc T. "How Do Regulators Regulate? Enforcement of the Pure Food and Drugs Act, 1907-38." Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 22, no. 2 (2006): 459-89.

Loeb, Lori. "Doctors and Patent Medicines in Modern Britain: Professionalism and Consumerism." Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies 33, no. 3 (2001): 404-25.

Moyers, David M. "From Quackery to Qualification: Arkansas Medical and Drug Legislation, 1881-1909." The Arkansas Historical Quarterly 35, no. 1 (1976): 3-26.

Myers, Robin, Michael Harris, and Giles Mandelbrote. Books for Sale: The Advertising and Promotion of Print Since the Fifteenth Century. New Castle, DE: Oak Knoll Press, 2009.

Parrish, Susan Scott.American Curiosity: Cultures of Natural History in the Colonial British Atlantic World. University of North Carolina Press, 2006.

Starr, Paul. "Medicine, Economy and Society in Nineteenth-Century America." Journal of Social History 10, no. 4 (1977): 588-607.

Tomes, Nancy. "Merchants of Health: Medicine and Consumer Culture in the United States, 1900-1940." The Journal of American History 88, no. 2 (2001): 519-47.

Whooley, Owen. Knowledge In The Time Of Cholera: The Struggle Over American Medicine In The Nineteenth Century. University of Chicago Press, 2013.

Wisecup, Kelly. “Good News From New England” by Edward Winslow: A Scholarly Edition.University of Massachusetts Press, 2014.

Wisecup, Kelly. Medical Encounters: Knowledge and Identity in Early American Literatures, University of Massachusetts Press, 2013.

Young, James Harvey. "American Medical Quackery in the Age of the Common Man." The Mississippi Valley Historical Review 47, no. 4 (1961): 579-93.

Young, James Harvey. "Food and Drug Regulation under the USDA, 1906-1940." Agricultural History 64, no. 2 (1990): 134-42.

Young, James Harvey. "Patent Medicines: An Early Example of Competitive Marketing." The Journal of Economic History 20, no. 4 (1960): 648-56.

Young, James Harvey. The Toadstool Millionaires: A Social History of Patent Medicines in America Before Federal Regulation. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, 1972.