Gift of rare Third Folio enhances UofSC’s Shakespeare collection

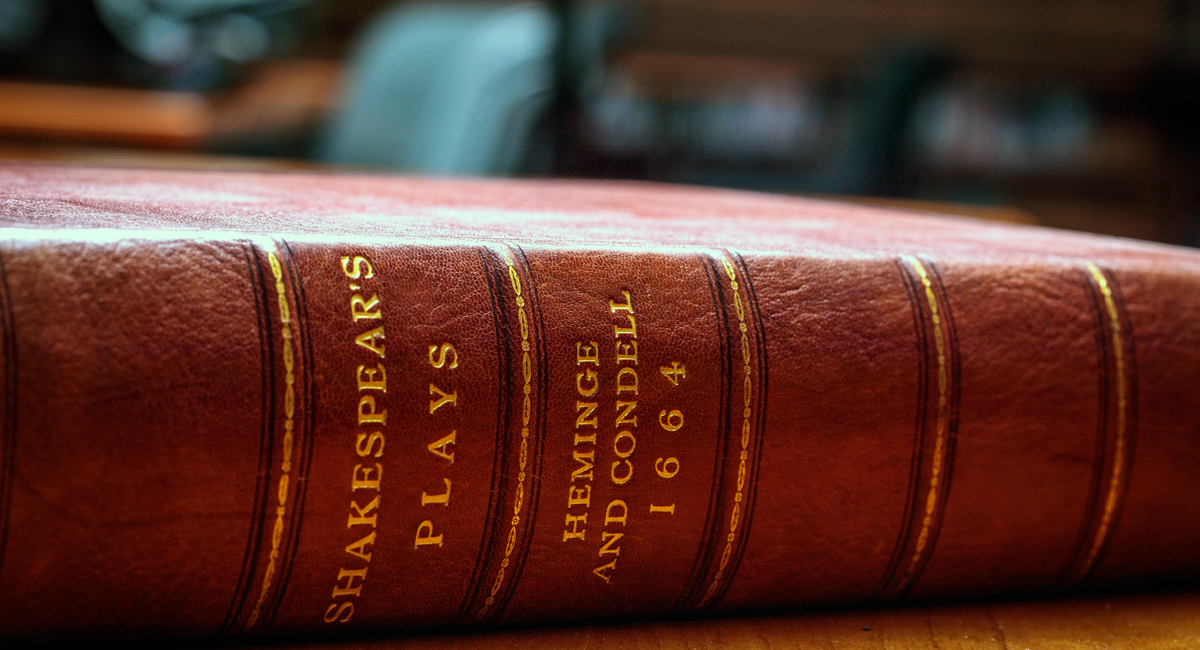

A Third Folio of Shakespeare’s plays printed in 1664 has a permanent home at University of South Carolina Libraries.

The book, a gift from Chicago attorney Jeffery Leving, along with the university’s copies of the Second and Fourth folios, will provide a rare opportunity for students, faculty and other researchers. Widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's greatest dramatist, Shakespeare produced most of his known works between 1589 and 1613.

“Scholars spend a good deal of time working with facsimiles and digital versions of Shakespeare’s plays, so the chance to work directly with archival materials is invaluable,” says Nina Levine, professor of English and associate dean of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences in the College of Arts and Sciences, who publishes widely on Shakespeare.

The three folios together also benefit UofSC students who will be able to study Shakespeare’s afterlife in print in the 75 years following his death, Levine adds.

Every copy of a Shakespeare Folio tells a piece of a larger story, and when these copies are brought together, interesting things start to take shape, says Greg Prickman, the Eric Weinmann librarian and director of collections for Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.

“The Third Folio is an important piece of the puzzle of how Shakespeare became the iconic figure he is today, and this evolution becomes apparent when the Second, Third, and Fourth folios can be studied alongside one another and their differences compared,” Prickman says.

'Third Folio is the rarest'

Many of Shakespeare’s plays, which were written to be performed, were not published during his lifetime. The First Folio, the first collected edition of Shakespeare’s works was published in 1623, seven years after his death, by two fellow actors who compiled 46 of his plays to preserve them for future generations. A Second Folio was published in 1632, and the Third Folio, which was published in 1663 and reissued in 1664, has been described as rare, compared with the Second and Fourth (1685). The reason for its rarity has been debated, but speculation is that many copies were destroyed in the Great Fire of London in 1666.

The second issue, is significant, Levine says, because it was published shortly after the theaters reopened following the Restoration, and it included seven so-called “new” plays. Shakespeare may have had a hand in some of these additional plays, but only Pericles is attributed to Shakespeare today.

“The Third Folio is the rarest of the folios. Having one in our collection provides a more enriching classroom and research experience for students. And it puts us in very good company. Harvard, Yale, Duke, Rutgers and Emory universities all have copies,” says Tom McNally, dean of University Libraries.

Fewer than 50 copies of the Third Folio are cataloged through the Online Computer Library Center, says Elizabeth Sudduth, associate dean for special collections and director of the Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections. Not all copies — such as those in private collections — are included in this global library cooperative, but it is an indication of the quantity in existence.

Looking over the shoulder of early readers

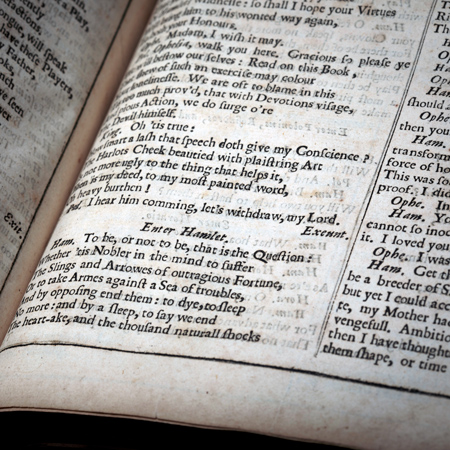

University Libraries' Third Folio includes markings that may tell researchers a little about previous readers.

UofSC’s copy has a few areas of restoration or repairs and some minor damage such as a few small wormholes or ash marks – imperfections you’d expect to see in a folio that’s been consulted and survived over 350 years, Sudduth says. There are also ink annotations and markings on the pages of three plays, Richard II, Henry V1 Part 3 and Henry VIII, which may have been made for a performance or reading.

“I’m especially interested this particular copy because it’s marked up and so gives us a glimpse of how 17th-century readers actually used Shakespeare,” Levine says. “For many years, collectors sought out pristine copies of Shakespeare folios, but now we’re interested in copies that Amazon would market as ‘used — may contain markings and some underlining.’ I’m very interested in what this copy tells us about those who left traces of their reading on the printed pages, commenting on and sometimes correcting what they read.”

She sees working with the folio as an opportunity to read over the shoulders of Shakespeare’s early readers, to see what they thought about while they read or to imagine what stories lie in their annotations.

Prickman agrees. “Books printed hundreds of years ago all contain evidence of where they’ve been and who has read them, and studying these aspects of each copy leads to new research discoveries,” he says. “The Third Folio is a fascinating book that is also different than the Second or Fourth Folio, and discovering how it is different is a wonderful teaching opportunity, and the first step toward new research discoveries.”

Sudduth says the gift is a great acquisition to enhance UofSC’s collections and fits well with the Second and Fourth folios. “We're about access and teaching with our materials, and this is good solid teaching copy that we can make accessible as a resource for students and researchers.”

Obtaining a First Folio is now near the top of University Libraries’ wish list.

“The acquisition of this copy moves the university closer to completing a full set,” McNally says. “We now have excellent copies of the Second, Third and Fourth folios. We hope to acquire a First in the future to complete the set and further add to the student experience.”

Learn more

Chicago attorney, author, artist and collector Jeffery M. Leving has a passion for collecting. Learn more about him and his gift of the rare Third Folio at University Libraries' website.